Inquisition

The Inquisition was a medieval Catholic judicial procedure where the ecclesiastical judges could initiate, investigate and try cases in their jurisdiction. Popularly it became the name for various State-organized tribunals whose aim was to combat heresy, apostasy, blasphemy, witchcraft, and other dangers, using this procedure. Studies of the records have found that the overwhelming majority of sentences consisted of penances, but convictions of unrepentant heresy were handed over to the secular courts for the application of local law, which generally resulted in execution or life imprisonment.[1][2][3] If the accused was known to be lying, a single short application of non-maiming torture was allowed, to corroborate evidence.[4][5]

Inquisitions with the aim of combating religious sedition (e.g. apostasy or heresy) had their start in the 12th-century Kingdom of France, particularly among the Cathars and the Waldensians. The inquisitorial courts from this time until the mid-15th century are together known as the Medieval Inquisition. Other banned groups investigated by medieval inquisitions, which primarily took place in France and Italy, include the Spiritual Franciscans, the Hussites, and the Beguines. Beginning in the 1250s, inquisitors were generally chosen from members of the Dominican Order, replacing the earlier practice of using local clergy as judges.[6]

Inquisitions also expanded to other European countries,[3] resulting in the Spanish Inquisition and the Portuguese Inquisition. The Spanish and Portuguese inquisitions often focused on the New Christians or Conversos (the former Jews who converted to Christianity to avoid antisemitic regulations and persecution), the Marranos (people who were forced to abandon Judaism against their will by violence and threats of expulsion) and on Muslim converts to Catholicism, as a result of suspicions that they had secretly reverted to their previous religions, as well as the fear of possible rebellions and armed uprisings, as had occurred in previous times. Spain and Portugal also operated inquisitorial courts not only in Europe, but also throughout their empires: the Goa Inquisition, the Peruvian Inquisition, and the Mexican Inquisition, among others.[7] Inquisitions conducted in the Papal States were known as the Roman Inquisition. With the exception of the Papal States, ecclessiastical inquisition courts were abolished in the early 19th century, after the Napoleonic Wars in Europe and the Spanish American wars of independence in the Americas.

The scope of the inquisitions grew significantly in response to the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation. In 1542, a putative governing institution, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition was created. The papal institution survived as part of the Roman Curia, although it underwent a series of name and focus changes.

The opening of Spanish and Roman archives over the last 50 years has caused historians to substantially revise their understanding of the Inquisition, some to the extent of viewing previous views as "a body of legends and myths".[8] Many famous instruments of torture are now considered fakes and propaganda.

Definition and goals

[edit]

Today, the English term "Inquisition" is popularly applied to any one of the regional tribunals or later national institutions that worked against heretics or other offenders against the canon law of the Catholic Church. Although the term "Inquisition" is usually applied to ecclesiastical courts of the Catholic Church, in the Middle Ages it properly referred to a judicial process, not any organization.

The term "Inquisition" comes from the Medieval Latin word inquisitio, which described a court process based on Roman law, which came back into use during the Late Middle Ages.[10] It was a new, less arbitrary form of trial that replaced the denunciatio and accussatio process[11] which required a denouncer or used an adversarial process, the most unjust being trial by ordeal and the secular Germanic trial by combat. These inquisitions, as church courts, had no jurisdiction over Muslims and Jews as such, to try or to protect them.

Inquisitors 'were called such because they applied a judicial technique known as inquisitio, which could be translated as "inquiry" or "inquest".' In this process, which was already widely used by secular rulers (Henry II used it extensively in England in the 12th century), an official inquirer called for information on a specific subject from anyone who felt he or she had something to offer."[12]

"The Inquisition" usually refers to specific regional tribunals authorized to concern themselves with the heretical behaviour of Catholic adherents or converts (including forced converts).[13] As with sedition inquisitions, heresy inquisitions were supposed to use the standard inquisition procedures: these included that the defendant must be informed of the charges, has a right to a lawyer, and a right of appeal (to the Pope.) The inquisitor could only start a heresy proceeding if there was some broad public opinion of the "infamy" of the defendant (rather than a formal denunciation or accusation) to prevent fishing, or charging for private opinions. However, such inquisitions could proceed with minimal distraction by lawyers, the identity of witnesses was protected, tainted witness were allowed, and once found guilty of heresy there was no right to a lawyer.[11] However, many inquisitors did not followed these rules scrupulously, notably from the late 1300s: many inquisitors had theological not legal training.[11]: 448

The overwhelming majority of guilty sentences with repentance seem to have consisted of penances like wearing a cross sewn on one's clothes or going on pilgrimage.[1] When a suspect was convicted of major, wilful, unrepentant heresy, canon law required the inquisitorial tribunal to hand the person over to secular authorities for final sentencing. A secular magistrate, the "secular arm", would then determine the penalty based on local law.[14][15] Those local laws included proscriptions against certain religious crimes, and the punishments included death by burning in regions where the secular law equated persistent heresy with sedition, although the penalty was more usually banishment or imprisonment for life, which was generally commuted after a few years. Thus the inquisitors generally knew the expected fate of anyone so remanded.[16] The "secular arm" didn't have access to the trial record of the defendants, only declared and executed the sentences and was obliged to do so on pain of heresy and excommunication.[17][18]

While the notational purpose of the trial itself was for the salvation of the individual by persuasion,[19] according to the 1578 edition of the Directorium Inquisitorum (a standard manual for inquisitions) the penalties themselves were preventative not retributive: ... quoniam punitio non refertur primo & per se in correctionem & bonum eius qui punitur, sed in bonum publicum ut alij terreantur, & a malis committendis avocentur (translation: "... for punishment does not take place primarily and per se for the correction and good of the person punished, but for the public good in order that others may become terrified and weaned away from the evils they would commit").[20]

Origin

[edit]Before the 12th century, the Catholic Church suppressed what they believed to be heresy, usually through a system of ecclesiastical proscription or imprisonment, but without using torture,[21] and seldom resorting to executions.[22][23] Such punishments were opposed by a number of clergymen and theologians, although some countries punished heresy with the death penalty.[24][3] Pope Siricius, Ambrose of Milan, and Martin of Tours protested against the execution of Priscillian, largely as an undue interference in ecclesiastical discipline by a civil tribunal. Though widely viewed as a heretic, Priscillian was executed as a sorcerer. Ambrose refused to give any recognition to Ithacius of Ossonuba, "not wishing to have anything to do with bishops who had sent heretics to their death".[25]

In the 12th century, to counter the spread of Catharism, and other heresies, prosecution of heretics became more frequent. The Church charged councils composed of bishops and archbishops with establishing inquisitions (the Episcopal Inquisition). Pope Lucius III issued the bull Ad Abolendam (1184), which condemned heresy as contumacy toward ecclesiastical authority. [26] The bull Vergentis in Senium in 1199 stipulated that heresy would be considered, in terms of punishment, equal to treason (Lèse-majesté), and the punishment would be imposed also on the descendants of the condemned.[27]

The first Inquisition was temporarily established in Languedoc (south of France) in 1184. The murder of Pope Innocent III's papal legate Pierre de Castelnau by Cathars in 1208 sparked the Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229). The Inquisition was permanently established in 1229 (Council of Toulouse), run largely by the Dominicans[28] in Rome and later at Carcassonne in Languedoc.

In 1252, the Papal Bull Ad extirpanda, following another assassination by Cathars, charged the head of state with funding and selecting inquisitors from monastic orders; this caused friction by establishing a competitive court to the Bishop's courts.

Medieval Inquisitions

[edit]Historians use the term "Medieval Inquisition" to describe the various inquisitions that started around 1184, including the Episcopal Inquisitions (1184–1230s) and later the Papal Inquisitions (1230s). These inquisitions responded to large popular movements throughout Europe considered apostate or heretical to Christianity, in particular the Cathars in southern France and the Waldensians in both southern France and northern Italy. Other inquisitions followed after these first inquisition movements. The legal basis for some inquisitorial activity came from Pope Innocent IV's papal bull Ad extirpanda of 1252, which authorized the use of tortures in certain circumstances by inquisitors for eliciting confessions and denunciations from heretics.[29] By 1256 Alexander IV's Ut negotium allowed the inquisitors to absolve each other if they used instruments of torture.[30][31]

In the 13th century, Pope Gregory IX (reigned 1227–1241) assigned the duty of carrying out inquisitions to the Dominican Order and Franciscan Order. By the end of the Middle Ages, England and Castile were the only large western nations without a papal inquisition. Most inquisitors were friars who taught theology and/or law in the universities. They used inquisitorial procedures, a common legal practice adapted from the earlier Ancient Roman court procedures. [10] They judged heresy along with bishops and groups of "assessors" (clergy serving in a role that was roughly analogous to a jury or legal advisers), using the local authorities to establish a tribunal and to prosecute heretics. After 1200, a Grand Inquisitor headed but did not control each regional Inquisition. Grand Inquisitions persisted until the mid 19th century.[32]

Inquisitions in Italy

[edit]Only fragmentary data is available for the period before the Roman Inquisition of 1542. In 1276, some 170 Cathars were captured in Sirmione, who were then imprisoned in Verona, and there, after a two-year trial, on February 13 from 1278, more than a hundred of them were burned.[33] In Orvieto, at the end of 1268/1269, 85 heretics were sentenced, none of whom were executed, but in 18 cases the sentence concerned people who had already died.[34] In Tuscany, the inquisitor Ruggiero burned at least 11 people in about a year (1244/1245).[35] Excluding the executions of the heretics at Sirmione in 1278, 36 Inquisition executions are documented in the March of Treviso between 1260 and 1308.[36] Ten people were executed in Bologna between 1291 and 1310.[37] In Piedmont, 22 heretics (mainly Waldensians) were burned in the years 1312–1395 out of 213 convicted.[37] 22 Waldensians were burned in Cuneo around 1440 and another five in the Marquisate of Saluzzo in 1510.[38] There are also fragmentary records of a good number of executions of people suspected of witchcraft in northern Italy in the 15th and early 16th centuries.[39] Wolfgang Behringer estimates that there could have been as many as two thousand executions.[40] This large number of witches executed was probably because some inquisitors took the view that the crime of witchcraft was exceptional, which meant that the usual rules for heresy trials did not apply to its perpetrators. Many alleged witches were executed even though they were first tried and pleaded guilty, which under normal rules would have meant only canonical sanctions, not death sentences.[41] The episcopal inquisition was also active in suppressing alleged witches: in 1518, judges delegated by the Bishop of Brescia, Paolo Zane, sent some 70 witches from Val Camonica to the stake.[42]

Inquisitions in France

[edit]

The Albigensian Crusade (1209–1229) a crusade proclaimed by the Catholic Church against heresy, mainly Catharism, with many thousands of victims (men, women and children, some of them Catholics), had already paved the way for the later Inquisition.[43][44]

France has the best preserved archives of medieval inquisitions (13th–14th centuries), although they are still very incomplete. The activity of the inquisition in this country was very diverse, both in terms of time and territory. In the first period (1233 to c. 1330), the courts of Languedoc (Toulouse, Carcassonne) are the most active. After 1330 the center of the persecution of heretics shifted to the Alpine regions, while in Languedoc they ceased almost entirely. In northern France, the activity of the inquisitors was irregular throughout this period and, except for the first few years, it was not very intense.[45]

France's first Dominican inquisitor, Robert le Bougre, working in the years 1233–1244, earned a particularly grim reputation. In 1236, Robert burned about 50 people in the area of Champagne and Flanders, and on May 13, 1239, in Montwimer, he burned 183 Cathars.[46] Following Robert's removal from office, Inquisition activity in northern France remained very low. One of the largest trials in the area took place in 1459–1460 at Arras; 34 people were then accused of witchcraft and satanism, 12 of them were burned at the stake.[47]

The main center of the medieval inquisition was undoubtedly the Languedoc. The first inquisitors were appointed there in 1233, but due to strong resistance from local communities in the early years, most sentences concerned dead heretics, whose bodies were exhumed and burned. Actual executions occurred sporadically and, until the fall of the fortress of Montsegur (1244), probably accounted for no more than 1% of all sentences.[48] In addition to the cremation of the remains of the dead, a large percentage were also sentences in absentia and penances imposed on heretics who voluntarily confessed their faults (for example, in the years 1241–1242 the inquisitor Pierre Ceila reconciled 724 heretics with the Church).[49] Inquisitor Ferrier of Catalonia, investigating Montauban between 1242 and 1244, questioned about 800 people, of whom he sentenced 6 to death and 20 to prison.[50] Between 1243 and 1245, Bernard de Caux handed down 25 sentences of imprisonment and confiscation of property in Agen and Cahors.[51] After the fall of Montsegur and the seizure of power in Toulouse by Count Alfonso de Poitiers, the percentage of death sentences increased to around 7% and remained at this level until the end of the Languedoc Inquisition around from 1330.[52]

Between 1245 and 1246, the inquisitor Bernard de Caux carried out a large-scale investigation in the area of Lauragais and Lavaur. He covered 39 villages, and probably all the adult inhabitants (5,471 people) were questioned, of whom 207 were found guilty of heresy. Of these 207, no one was sentenced to death, 23 were sentenced to prison and 184 to penance.[53] Between 1246 and 1248, the inquisitors Bernard de Caux and Jean de Saint-Pierre handed down 192 sentences in Toulouse, of which 43 were sentences in absentia and 149 were prison sentences.[54]

In Pamiers in 1246/1247 there were 7 prison sentences [201] and in Limoux in the county of Foix 156 people were sentenced to carry crosses.[55] Between 1249 and 1257, in Toulouse, the inquisitors handed down 306 sentences, without counting the penitential sentences imposed during "times of grace". 21 people were sentenced to death, 239 to prison, in addition, 30 people were sentenced in absentia and 11 posthumously; In another five cases the type of sanction is unknown, but since they all involve repeat offenders, only prison or burning is at stake.[56] Between 1237 and 1279, at least 507 convictions were passed in Toulouse (most in absentia or posthumously) resulting in the confiscation of property; in Albi between 1240 and 1252 there were 60 sentences of this type.[57]

The activities of Bernard Gui, inquisitor of Toulouse from 1307 to 1323, are better documented, as a complete record of his trials has been preserved. During the entire period of his inquisitorial activity, he handed down 633 sentences against 602 people (31 repeat offenders), including:

- 41 death sentences,

- 40 convictions of fugitive heretics (in absentia),

- 20 sentences against people who died before the end of the trial (3 of them Bernardo considered unrepentant, and his remains were burned at the stake),

- 69 exhumation orders for the remains of dead heretics (66 of whom were subsequently burned),

- 308 prison sentences, with confiscation of property,

- 136 orders to carry crosses,

- 18 mandates to make a pilgrimage (17) or participate in a crusade (1),

- in one case, sentencing was postponed.

In addition, Bernard Gui issued 274 more sentences involving the mitigation of sentences already served to convicted heretics; in 139 cases he exchanged prison for carrying crosses, and in 135 cases, carrying crosses for pilgrimage. To the full statistics, there are 22 orders to demolish houses used by heretics as meeting places and one condemnation and burning of Jewish writings (including commentaries on the Torah).[58]

The episcopal inquisition was also active in Languedoc. In the years 1232–1234, the Bishop of Toulouse, Raymond, sentenced several dozen Cathars to death. In turn, Bishop Jacques Fournier of Pamiers (he was later Pope Benedict XII) in the years 1318–1325 conducted an investigation against 89 people, of whom 64 were found guilty and 5 were sentenced to death.[59]

After 1330, the center of activity of the French inquisitions moved east, to the Alpine regions, where there were numerous Waldensian communities. The repression against them was not continuous and was very ineffective. Data on sentences issued by inquisitors are fragmentary. In 1348, 12 Waldensians were burned in Embrun, and in 1353/1354 as many as 168 received penances.[60] In general, however, few Waldensians fell into the hands of the inquisitors, for they took refuge in hard-to-reach mountainous regions, where they formed close-knit communities. Inquisitors operating in this region, in order to be able to conduct trials, often had to resort to the armed assistance of local secular authorities (e.g. military expeditions in 1338–1339 and 1366). In the years 1375–1393 (with some breaks), the Dauphiné was the scene of the activities of the inquisitor Francois Borel, who gained an extremely gloomy reputation among the locals. It is known that on July 1, 1380, he pronounced death sentences in absentia against 169 people, including 108 from the Valpute valley, 32 from Argentiere and 29 from Freyssiniere. It is not known how many of them were actually carried out, only six people captured in 1382 are confirmed to be executed.[61]

In the 15th and 16th centuries, major trials took place only sporadically, e.g. against the Waldensians in Delphinate in 1430–1432 (no numerical data) and 1532–1533 (7 executed out of about 150 tried) or the aforementioned trial in Arras 1459–1460 . In the 16th century, the jurisdiction of the inquisitors in the kingdom of France was effectively limited to clergymen, while local parliaments took over the jurisdiction of the laity. Between 1500 and 1560, 62 people were burned for heresy in the Languedoc, all of whom were convicted by the Parliament of Toulouse.[62]

Between 1657 and 1659, twenty-two alleged witches were burned on the orders of the inquisitor Pierre Symard in the province of Franche-Comté, then part of the Empire.[63]

The inquisitorial tribunal in papal Avignon, established in 1541, passed 855 death sentences, almost all of them (818) in the years 1566–1574, but the vast majority of them were pronounced in absentia.[64]

Inquisitions in Germany

[edit]The Rhineland and Thuringia in the years 1231–1233 were the field of activity of the notorious inquisitor Konrad of Marburg. Unfortunately, the documentation of his trials has not been preserved, making it impossible to determine the number of his victims. The chronicles only mention "many" heretics that he burned. The only concrete information is about the burning of four people in Erfurt in May 1232.[65]

After the murder of Konrad of Marburg, burning at the stake in Germany was virtually unknown for the next 80 years. It was not until the early fourteenth century that stronger measures were taken against heretics, largely at the initiative of bishops. In the years 1311–1315, numerous trials were held against the Waldensians in Austria, resulting in the burning of at least 39 people, according to incomplete records.[66] In 1336, in Angermünde, in the diocese of Brandenburg, another 14 heretics were burned.[67]

The number of those convicted by the papal inquisitors was smaller.[68] Walter Kerlinger burned 10 begards in Erfurt and Nordhausen in 1368–1369. In turn, Eylard Schöneveld burned a total of four people in various Baltic cities in 1402–1403.[69]

In the last decade of the 14th century, episcopal inquisitors carried out large-scale operations against heretics in eastern Germany, Pomerania, Austria, and Hungary. In Pomerania, of 443 sentenced in the years 1392–1394 by the inquisitor Peter Zwicker, the provincial of the Celestinians, none went to the stake, because they all submitted to the Church. Bloodier were the trials of the Waldensians in Austria in 1397, where more than a hundred Waldensians were burned at the stake. However, it seems that in these trials the death sentences represented only a small percentage of all the sentences, because according to the account of one of the inquisitors involved in these repressions, the number of heretics reconciled with the Church from Thuringia to Hungary amounted to about 2,000.[70]

In 1414, the inquisitor Heinrich von Schöneveld arrested 84 flagellants in Sangerhausen, of whom he burned 3 leaders, and imposed penitential sentences on the rest. However, since this sect was associated with the peasant revolts in Thuringia from 1412, after the departure of the inquisitor, the local authorities organized a mass hunt for flagellants and, regardless of their previous verdicts, sent at least 168 to the stake (possibly up to 300) people.[71] Inquisitor Friedrich Müller (d. 1460) sentenced to death 12 of the 13 heretics he had tried in 1446 at Nordhausen. In 1453 the same inquisitor burned 2 heretics in Göttingen.[72]

Inquisitor Heinrich Kramer, author of the Malleus Maleficarum, in his own words, sentenced 48 people to the stake in five years (1481–1486).[73][74] Jacob Hoogstraten, inquisitor of Cologne from 1508 to 1527, sentenced four people to be burned at the stake.[75]

A duke of Brunswick in German was so shocked by the methods used by Inquisitors in his realm that he asked two famous Jesuit scholars to supervise. After careful study, the two 'told the Duke, "The Inquisitors are doing their duty. They are arresting only people who have been implicated by the confession of other witches."' The Duke then led the Jesuits to a woman being stretched on the rack and asked her, "You are a confessed witch. I suspect these two men of being warlocks. What do you say? Another turn of the rack, executioners." "No, no!" screamed the woman. "You are quite right. I have often seen .. . They can turn themselves into goats, wolves, and other animals. ... Several witches have had children by them. ... The children had heads like toads and legs like spiders." The Duke then asked the Jesuits. "Shall I put you to the torture until you confess, my friends?" One of the Jesuits was Friedrich Spee, who thanked God he had been led to this insight by a friend, not an enemy.[76]

Inquisition in Hungary and the Balkans

[edit]Very little is known about the activities of inquisitors in Hungary and the countries under its influence (Bosnia, Croatia), as there are few sources about this activity.[77] Numerous conversions and executions of Bosnian Cathars are known to have taken place around 1239/40, and in 1268 the Dominican inquisitor Andrew reconciled many heretics with the Church in the town of Skradin, but precise figures are unknown.[78] The border areas with Bohemia and Austria were under major inquisitorial action against the Waldensians in the early 15th century. In addition, in the years 1436–1440 in the Kingdom of Hungary, the Franciscan Jacobo de la Marcha acted as an inquisitor... his mission was mixed, preaching and inquisitorial. The correspondence preserved between James, his collaborators, the Hungarian bishops and Pope Eugene IV shows that he reconciled up to 25,000 people with the Church. This correspondence also shows that he punished recalcitrant heretics with death, and in 1437 numerous executions were carried out in the diocese of Sirmium, although the number of those executed is also unknown.[79]

Inquisitions in the Czech Republic and Poland

[edit]In Bohemia and Poland, the inquisition was established permanently in 1318, although anti-heretical repressions were carried out as early as 1315 in the episcopal inquisition, when more than 50 Waldensians were burned in various Silesian cities.[80] The fragmentary surviving protocols of the investigations carried out by the Prague inquisitor Gallus de Neuhaus in the years 1335 to around 1353 mention 14 heretics burned out of almost 300 interrogated, but it is estimated that the actual number executed could have been even more than 200, and the entire process was covered to varying degrees by some 4,400 people.[81]

In the lands belonging to the Kingdom of Poland little is known of the activities of the Inquisition until the appearance of the Hussite heresy in the 15th century. Polish courts of the inquisition in the fight against this heresy issued at least 8 death sentences for some 200 trials carried out.[82]

There are 558 court cases finished with conviction researched in Poland from the 15th to 18th centuries.[83]

Inquisition in Spain

[edit]Portugal and Spain in the late Middle Ages consisted largely of multicultural territories of Muslim and Jewish influence, reconquered from Islamic control, and the new Christian authorities could not assume that all their subjects would suddenly become and remain orthodox Catholics. So the Inquisition in Iberia, in the lands of the Reconquista counties and kingdoms like León, Castile, and Aragon, had a special socio-political basis as well as more fundamental religious motives.[84]

In some parts of Spain towards the end of the 14th century, there was a wave of violent anti-Judaism, encouraged by the preaching of Ferrand Martínez, Archdeacon of Écija. In the pogroms of June 1391 in Seville, hundreds of Jews were killed, and the synagogue was completely destroyed. The number of people killed was also high in other cities, such as Córdoba, Valencia, and Barcelona.[85]

One of the consequences of these pogroms was the mass conversion of thousands of surviving Jews. Forced baptism was contrary to the law of the Catholic Church, and theoretically anybody who had been forcibly baptized could legally return to Judaism. However, this was very narrowly interpreted. Legal definitions of the time theoretically acknowledged that a forced baptism was not a valid sacrament, but confined this to cases where it was literally administered by physical force. A person who had consented to baptism under threat of death or serious injury was still regarded as a voluntary convert, and accordingly forbidden to revert to Judaism.[86] After the public violence, many of the converted "felt it safer to remain in their new religion".[87] Thus, after 1391, a new social group appeared and were referred to as conversos or New Christians.

Manuals for inquisitors

[edit]Over the centuries that it lasted, several procedure manuals for inquisitors were produced for dealing with different types of heresy. The primordial text was Pope Innocent IV's bull, Ad Extirpanda, from 1252, which in its thirty-eight laws details in detail what must be done and authorizes the use of torture.[88] Of the various manuals produced later, some stand out: by Nicholas Eymerich, Directorium Inquisitorum, written in 1376; by Bernardo Gui, Practica inquisitionis heretice pravitatis, written between 1319 and 1323. Witches were not forgotten: the book Malleus Maleficarum ("the witches' hammer"), written in 1486, by Heinrich Kramer, deals with the subject. [89]

In Portugal, several "Regimentos" (four) were written for the use of the inquisitors, the first in 1552 at the behest of the inquisitor Cardinal D. Henrique and the last in 1774, this sponsored by the Marquis of Pombal. The Portuguese 1640 Regiment determined that each court of the Holy Office should have a Bible, a compendium of canon and civil law, Eymerich's Directorium Inquisitorum, and Diego de Simancas' Catholicis institutionibus.[89]

In 1484, Spanish inquisitor Torquemada, based in Nicholas Eymerich's Directorium Inquisitorum, wrote his twenty eight articles code, Compilación de las instrucciones del oficio de la Santa Inquisición (i.e. Compilation of the instructions of the office of the Holy Inquisition). Later additions would be made, based on experience, many by the canonist Francisco Peña.[90][91]

Early modern European history

[edit]

With the sharpening of debate and of conflict between the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Protestant societies came to see/use the Inquisition as a terrifying "other",[92] while staunch Catholics regarded the Holy Office as a necessary bulwark against the spread of reprehensible heresies. Since the beginning of the most serious heretic groups, like the Cathars or the Waldensians, they were soon accused of the most fantastic behavior, like having wild sexual orgies, eating babies, copulating with demons, worshipping the Devil.[93][94][95][96]

Witch-hunts

[edit]The fierce denunciation and persecution of supposed sorceresses that characterized the cruel witchhunts of a later age were not generally found in the first thirteen hundred years of the Christian era.[97] While belief in witchcraft, and persecutions directed at or excused by it, were widespread in pre-Christian Europe, and reflected in old Germanic law, the growing influence of the Church in the early medieval era in pagan areas resulted in the revocation of these laws in many places, bringing an end to the traditional witch hunts.[98] Throughout the medieval era, mainstream Christian teaching had disputed the existence of witches and denied any power to witchcraft, condemning it as pagan superstition.[99]

Black magic practitioners were generally dealt with through confession, repentance, and charitable work assigned as penance.[100] In 1258, Pope Alexander IV ruled that inquisitors should limit their involvement to those cases in which there was some clear presumption of heretical belief [101] but slowly this vision changed.[102]

The prosecution of witchcraft generally became more prominent in the late medieval and Renaissance era, perhaps driven partly by the upheavals of the era – the Black Death, the Hundred Years War, and a gradual cooling of the climate that modern scientists call the Little Ice Age (between about the 15th and 19th centuries). Witches were sometimes blamed.[103][104] Since the years of most intense witch-hunting largely coincide with the age of the Protestant Reformation and Counter-Reformation, some historians point to the influence of the Reformation on the European witch-hunt. However, witch-hunting began almost one hundred years before Luther's ninety-five theses.[105]

Malleus Maleficarum

[edit]Dominican priest Heinrich Kramer was assistant to the Archbishop of Salzburg, a sensational preacher, and an appointed local inquisitor. Historian Malcolm Gaskill calls Kramer a "superstitious psychopath".[106]

In 1484 Kramer requested that Pope Innocent VIII clarify his authority to conduct inquisitions into witchcraft throughout Germany, where he had been refused assistance by the local ecclesiastical authorities. They maintained that Kramer could not legally function in their areas.[107] Despite some support[108] from Pope Innocent VIII,[109] he was expelled from the city of Innsbruck by the local bishop, George Golzer, who ordered Kramer to stop making false accusations.

Golzer described Kramer as senile in letters written shortly after the incident. This rebuke led Kramer to write a justification of his views on witchcraft in his 1486 book Malleus Maleficarum ("Hammer against witches").[97] The book distinguishes itself from other demonologies by its obsessive hate of women and sex, seemingly reflecting the twisted psyche of the author.[110][111] Historian Brian Levack calls it "scholastic pornography".[111]

Despite Kramer's claim that the book gained acceptance from the clergy at the University of Cologne, it was in fact condemned by the clergy at Cologne for advocating views that violated Catholic doctrine and standard inquisitorial procedure. In 1538 the Spanish Inquisition cautioned its members not to believe everything the Malleus said.[112] Despite this, Heinrich Kramer was never excommunicated and even enjoyed considerable prestige till his death. [113][114]

Spanish Inquisition

[edit]

King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile established the Spanish Inquisition in 1478. In contrast to the previous inquisitions, it operated completely under royal Christian authority, though staffed by clergy and orders, and independently of the Holy See. It operated in Spain and in most[116] Spanish colonies and territories, which included the Canary Islands, the Kingdom of Sicily,[117] and all Spanish possessions in North, Central, and South America. It primarily focused upon forced converts from Islam (Moriscos, Conversos, and "secret Moors") and from Judaism (Conversos, Crypto-Jews, and Marranos)—both groups still resided in Spain after the end of the Islamic control of Spain—who came under suspicion of either continuing to adhere to their old religion or of having fallen back into it.

All Jews who had not converted were expelled from Spain in 1492, and all Muslims ordered to convert in different stages starting in 1501.[118] Those who converted or simply remained after the relevant edict became nominally and legally Catholics, and thus subject to the Inquisition.

Inquisition in the Spanish overseas empire

[edit]In 1569, King Philip II of Spain set up three tribunals in the Americas (each formally titled Tribunal del Santo Oficio de la Inquisición): one in Mexico, one in Cartagena de Indias (in modern-day Colombia), and one in Peru. The Mexican office administered Mexico (central and southeastern Mexico), Nueva Galicia (northern and western Mexico), the Audiencias of Guatemala (Guatemala, Chiapas, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica), and the Spanish East Indies. The Peruvian Inquisition, based in Lima, administered all the Spanish territories in South America and Panama.[119]

Portuguese Inquisition

[edit]

The Portuguese Inquisition formally started in Portugal in 1536 at the request of King João III. Manuel I had asked Pope Leo X for the installation of the Inquisition in 1515, but only after his death in 1521 did Pope Paul III acquiesce. At its head stood a Grande Inquisidor, or General Inquisitor, named by the Pope but selected by the Crown, and always from within the royal family.[citation needed] The Portuguese Inquisition principally focused upon the Sephardi Jews, whom the state forced to convert to Christianity. Spain had expelled its Sephardi population in 1492; many of these Spanish Jews left Spain for Portugal but eventually were subject to inquisition there as well.

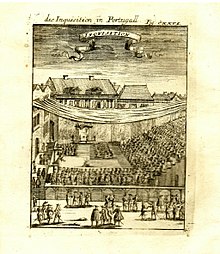

The Portuguese Inquisition held its first auto-da-fé in 1540. The Portuguese inquisitors mostly focused upon the Jewish New Christians (i.e. conversos or marranos). The Portuguese Inquisition expanded its scope of operations from Portugal to its colonial possessions, including Brazil, Cape Verde, and Goa. In the colonies, it continued as a religious court, investigating and trying cases of breaches of the tenets of orthodox Catholicism until 1821. King João III (reigned 1521–57) extended the activity of the courts to cover censorship, divination, witchcraft, and bigamy. Originally oriented for a religious action, the Inquisition exerted an influence over almost every aspect of Portuguese society: political, cultural, and social.

According to Henry Charles Lea, between 1540 and 1794, tribunals in Lisbon, Porto, Coimbra, and Évora resulted in the burning of 1,175 persons, the burning of another 633 in effigy, and the penancing of 29,590.[120] But documentation of 15 out of 689 autos-da-fé has disappeared, so these numbers may slightly understate the activity.[121]

Inquisition in the Portuguese overseas empire

[edit]Goa Inquisition

[edit]The Goa Inquisition began in 1560 at the order of John III of Portugal. It had originally been requested in a letter in the 1540s by Jesuit priest Francis Xavier, because of the New Christians who had arrived in Goa and then reverted to Judaism. The Goa Inquisition also focused upon Catholic converts from Hinduism or Islam who were thought to have returned to their original ways. In addition, this inquisition prosecuted non-converts who broke prohibitions against the public observance of Hindu or Muslim rites or interfered with Portuguese attempts to convert non-Christians to Catholicism.[122] Aleixo Dias Falcão and Francisco Marques set it up in the palace of the Sabaio Adil Khan.

Brazilian Inquisition

[edit]The inquisition was active in colonial Brazil. The religious mystic and formerly enslaved prostitute, Rosa Egipcíaca was arrested, interrogated and imprisoned, both in the colony and in Lisbon. Egipcíaca was the first black woman in Brazil to write a book – this work detailed her visions and was entitled Sagrada Teologia do Amor Divino das Almas Peregrinas.[123]

Roman Inquisition

[edit]With the Protestant Reformation, Catholic authorities became much more ready to suspect heresy in any new ideas,[124] including those of Renaissance humanism,[125] previously strongly supported by many at the top of the Church hierarchy. The extirpation of heretics became a much broader and more complex enterprise, complicated by the politics of territorial Protestant powers, especially in northern Europe. The Catholic Church could no longer exercise direct influence in the politics and justice-systems of lands that officially adopted Protestantism. Thus war (the French Wars of Religion, the Thirty Years' War), massacre (the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre) and the missional[126] and propaganda work (by the Sacra congregatio de propaganda fide)[127] of the catholic Counter-Reformation came to play larger roles in these circumstances, and the Roman law type of a "judicial" approach to heresy represented by the Inquisition became less important overall. In 1542 Pope Paul III established the Congregation of the Holy Office of the Inquisition as a permanent congregation staffed with cardinals and other officials. It had the tasks of maintaining and defending the integrity of the faith and of examining and proscribing errors and false doctrines; it thus became the supervisory body of local Inquisitions.[128] A famous case tried by the Roman Inquisition was that of Galileo Galilei in 1633.

The penances and sentences for those who confessed or were found guilty were pronounced together in a public ceremony at the end of all the processes. This was the sermo generalis or auto-da-fé.[129] Penances (not matters for the civil authorities) might consist of pilgrimages, a public scourging, a fine, or the wearing of a cross. The wearing of two tongues of red or other brightly colored cloth, sewn onto an outer garment in an "X" pattern, marked those who were under investigation. The penalties in serious cases were confiscation of property by the Inquisition or imprisonment. This led to the possibility of false charges to enable confiscation being made against those over a certain income, particularly rich marranos. Following the French invasion of 1798, the new authorities sent 3,000 chests containing over 100,000 Inquisition documents to France from Rome.[citation needed]

Inquisition Proceedings

[edit]Denunciations

[edit]The usual procedure began with the visitation by the inquisitors in a chosen location. The so-called heretics were then asked to be present and denounce themselves and others; it was not enough to denounce himself as a heretic.[130][131]

Many confessed alleged heresies for fear that a friend or neighbor might do so later. The terror of the Inquisition provoked chain reactions and denunciations[132] even of spouses, children and friends.[133]

If they confessed within a "grace period" — usually 30 days — they could be accepted back into the church without punishment. In general, the benefits proposed by the "edicts of grace" to those who presented themselves spontaneously were the forgiveness of the death penalty or life imprisonment and the forgiveness of the penalty of confiscation of property.[134]

Anyone suspected of knowing about another's heresy and who did not make the obligatory denunciation would be excommunicated and then subject to prosecution as a "promoter of heresy."[135] If the denouncer named other potential heretics, they would also be summoned. All types of complaints were accepted by the Inquisition, regardless of the reputation or position of the complainant. Rumors, mere suppositions, and even anonymous letters were accepted, "if the case were of such a nature that such action seemed appropriate to the service of God and the good of the Faith".[136] It was foreseen that prison guards themselves could report and be witnesses against the accused.[137]

This strategy transformed everyone into an Inquisition agent, reminding them that a simple word or deed could bring them before the tribunal. Denunciation was elevated to the status of a superior religious duty, filling the nation with spies and making every individual suspicious of his neighbor, family members, and any strangers he might met.[138]

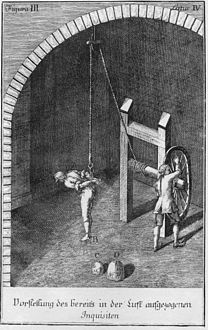

Methods of torture used

[edit]The primary method of torture was psychological: solitary confinement and indefinite incarceration.

Defendants were interrogated under physical torture only in extreme cases. The view of historian Ron E. Hassner is 'inquisitors knew that information obtained through torture often was not reliable. [So] They built their cases patiently, gathering information from a variety of sources, using a variety of methods. With any given subject, they used torture only intermittently, in sessions sometimes months apart. Their main goal was not to compel a confession or a profession of faith, but to extract factual information that would confirm or corroborate information already in hand.'[5]

The summary of the Directorium Inquisitorum, by Nicolás Aymerich, made by Marchena, notes a comment by the Aragonese inquisitor: Quaestiones sunt fallaces et inefficaces ("The interrogations are misleading and useless"). [139][140]

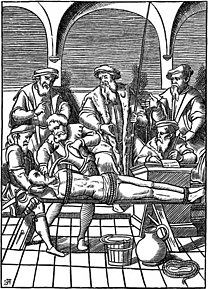

Defendants were punished if found guilty, with their property being confiscated to cover legal and prison costs and to maintain the extensive machinery of persecution. The victims could also repent of their accusation and receive reconciliation with the Church. The execution of the tortures was attended by the inquisitor, the doctor, the secretary and the torturer, applying them on the nearly naked prisoner. In the year 1252, the bull Ad extirpanda allowed torture, but always with a doctor involved to avoid endangering life, and limited its use to non-bloody methods that did not break bones:[141][142][143]

- Strappado: the victim was lifted to the ceiling with his arms tied behind his back, and then dropped violently, but without touching the ground. This usually meant the dislocation of the victim's arms.[144][145]

- Rack or potro: the prisoner was tied to a frame and the executioner pressed, but stopping before or if the meat was pierced or blood flowed. In another version, the victim was stretched on a sort of table, usually with serious impact in later life.[145][144][146][147] Many inquisitors believed the rack was not allowed.[11]

- Water cure, now known as water boarding: the prisoner was tied, a cloth was inserted through his mouth down to his throat, and one liter jugs of water were poured in to his mouth. The victim had the sensation of drowning, and the stomach swelled until near bursting.[148][149][150]

According to Catholic apologists, the method of torture (which was socially accepted in the context of the time) was adopted only in exceptional cases, and the inquisitorial procedure was meticulously regulated in interrogation practices.[151]

- Torture could not endanger the subject's life.[151]

- Torture could not cause the subject to lose a limb.[151]

- Torture could only be applied once, and only if the subject appeared to be lying.[151]

- Howwever, according to journalist Cullen Murphy, in practice torture was repeated or "continued".[156] The Portuguese instructions (Regimentos) stipulate that defendants may not appear at autos de fé showing marks of torture, so did not recommend using torture other than potro in the previous fortnight.[157][155]

Despite the loss of thousands of documents over the years, many of the meticulous records of torture sessions have survived.[156]

Fake instruments of torture

[edit]Despite what is popularly believed, the cases in which torture was used during the inquisitorial processes were rare, since it was considered (according to some authors) to be ineffective in obtaining evidence.[158][151] Before torture, some inquisitors may have displayed the instruments mainly on the purpose of intimidation of the accused, so he may understood what to expect. If he wished to avoid punishment, he should only confess his faults.[159][160][156]

In the words of historian Helen Mary Carrel: "the common view of the medieval justice system as cruel and based on torture and execution is often unfair and inaccurate."[161] As the historian Nigel Townson wrote: "The sinister torture chambers equipped with cogwheels, bone crushing contraptions, shackles, and other terrifying mechanisms only existed in the imagination of their detractors."[162]

In fact, it seems likely that the inquisitors favoured simpler and "cleaner" methods, which left few apparent marks. Aymerich points out that canon law does not prescribe either this or that particular torture, so judges can use whatever they see fit, as long as it's not an unusual torture. Many types of torments have been chosen, but Eymerich think they seem more like the inventions of executioners than the works of theologians. "It is true that it is a very praiseworthy practice to subject the accused to torture, but no less reprehensible are those bloodthirsty judges who base their vain glory on the invention of crude and exquisite torments" – he adds.[163]

Many torture instruments were designed by late 18th and early 19th century pranksters, entertainers, and con artists who wanted to profit from people's morbid interest in the Dark Age myth by charging them to witness such instruments in Victorian-era circuses.[164][165]

However, several torture instruments are accurately described in Foxe's Book of Martyrs, including but not limited to the dry pan.[166]

Some of the instruments that "the Inquisition" never used, but that are erroneously registered in various inquisition museums:[167]

- The troublemaker's flute:[168] Created in the 17th century. Its first mention comes from the years 1680–90 of the Republic of Venice used against deserters from the war between the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Venice.[citation needed]

- Head crusher: Created in the 14th century. Its first mention comes from 1340 in Germany. It was not used by the Inquisition but by the German courts against the enemies of some prince-electors.

- Judas's cradle: Created in the fifteenth century. Its first mention comes from 1450 to 1480 in France. Used by the parlement and not by the Inquisition, it was abolished in 1430.[citation needed]

- The Spanish donkey: Created in the 16th century. The name connects the instrument to the Spanish Inquisition, although it was only used in certain regions, which were not primarily Spain nor as part of the Inquisition, but by Central European civil authorities (most notably Reformed Germany and the Bohemian Crown), New France, the Netherlands Antilles, the British Empire, and the United States. It is unclear exactly who invented this device, and it is likely that it was ascribed to Spain as "Black Legend" propaganda.

- The Spanish tickle: Created in 2005 as a false rumor on Wikipedia.[164]

- The Thumbscrew: Created in the 16th century.[169] It was used for the persecution of Catholics by William Cecil in England during the reign of Elizabeth I. It was not used by the Inquisition, but by the English courts against dissidents to the Protestant Reformation,[citation needed] later also for the torture of slaves.[170]

- The saw: Created in the fifteenth century. Its first mention comes from 1450 to 1470. Used by the Hungarian court against Muslims in the context of the war between the Ottoman Empire, the Byzantine Empire and the Kingdom of Hungary.[171]

- Pear of anguish: Created in the fifteenth century. Its first mention comes from 1450. Used by the French parlement and not by the Inquisition, it was abolished in 1430.[172] The historian Chris Bishop came to postulate that it could have actually been a sock stretcher, since it has been proven that it was too weak to open into a body orifice.[173]

- The Spanish Boot: Created in the 14th century. Its first mentions come from Scotland with the buskin. Used by the authorities in England to persecute Catholics in Ireland. Later the civil authorities of France and Venice would use it, but not by the Spanish Inquisition.

- The "Cloak of Infamy". Created in the 17th century. It was first mentioned by Johann Philipp Siebenkees in 1790, and was used by the Nuremberg parliament (Protestant) against thieves and prostitutes.[citation needed]

- The Iron Maiden. The use of iron maidens in judicial proceedings or executions is doubted.[174] Several replicas of the Iron Maiden existed, and the one of Nuremberg Castle was destroyed in 1944 as a result of bombing during World War II. It was probably based on the 17th century Cloak of Infamy.[175]

- The Breast ripper. Created at the end of the 16th century. The first reference dates back to Bavaria (Germany) in 1599 and presumably it would have been used in France and Holy Roman Empire by civil authorities and not by the Inquisition. However, there are no reliable first-hand historical sources on the use of the devices, so, like the Iron Maiden, there is a possibility that the devices shown in the images are fakes of a later manufacture (such as from the 17th century) or assembled from small fragments that may have been parts of another device. Most likely, it was often mentioned to frighten and force the accused to confess, rather than such dubiously existent torture being inflicted on them.[176]

- The Stocks. Created in the Middle Ages and used by the civil authorities of London, not the Inquisition, in order to publicly shame criminals, but not physically harm them or take life.

- The bronze bull. Created in the Ancient Age and never used in medieval Europe, much less in the Inquisition. In fact, there is a chance that it never existed at all and was just a popular legend of Greco-Latin culture.

- The Scold's bridle. Created in the 16th century. It was never legalized and was only used unofficially by some civilians in Scotland and England, not by the Inquisition.

- The dungeon of rats. Created in the 16th century, its main reference is from John Lothrop Motley about some anecdotes of torture against the "papists" during the Dutch war of independence. It is also said that Catholics who resisted the Church of England under Elizabeth I were tortured in the Tower of London.[177] Used by some Protestant governments and not by the Inquisition.[178]

- Heretic's Fork, Boots, Cat's Paw, and Iron Cage. Created in the 15th–16th century. Used by the French parlement and not by the Inquisition.[citation needed]

Trials

[edit]This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (October 2024) |

The Inquisition's trials were secret and there was no possibility of appealing the decisions.[dubious – discuss] The defendant was constantly pressured to confess to the "crimes" assigned to him. The Inquisitors kept the accusations made and the evidence they possessed hidden, in order to achieve a confession without announcing the accusation.[179][dubious – discuss] The main goal was to make the defendant confess.

Each court had its own staff (lawyers, prosecutors, notaries, etc.) and its own prison. The guards who served the inquisition spied the accused in their cells; if they refused to eat, for example, this action could be considered a fast, a Jewish custom.[180]

In many cases, it was common for false accusations to be made against New Christians and it was difficult to prove their innocence. It was therefore more convenient for many to make a false confession to the inquisitors, including a list of imaginary accomplices, in the hope that they would not receive extreme penalties, such as the death penalty, but only the confiscation of property or lesser penalties.[181]

In fact, there wasn't a trial in the modern sense of the term, but an extensive interrogation;[dubious – discuss] the prisoner was kept in the dark about the reasons for his arrest — often for months or even years. There was no precise accusation and therefore little chance of a plausible defence. The prisoner was simply advised "to search his conscience, confess the truth, and trust to the mercy of the tribunal'".[182]

Eventually, the prisoner was informed of the charges against him — omitting the names of the witnesses. Thus, the charade continued.[182][dubious – discuss] After the interminable interrogations, hearings and waiting periods came to an end, the sentence could be pronounced.[183]

The Inquisition trials had little to do with justice. Walter Ullmann, a historian, summarises his evaluation: "There is hardly one item in the whole Inquisitorial procedure that could be squared with the demands of justice; on the contrary, every one of its items is the denial of justice or a hideous caricature of it [...] its principles are the very denial of the demands made by the most primitive concepts of natural justice [...] This kind of proceeding has no longer any semblance to a judicial trial but is rather its systematic and methodical perversion."[184]

In one of his books, Portuguese author A. José Saraiva points out the analogy of the trials with the absurdity of the Kafka's novel The Trial or the show trials of Stalin's era in Moscow.[185]

Punishments

[edit]The Inquisition's sentences could be simple penances, for example private devotions, or heavy punishments. One of the Inquisition's punishments was the forced wearing of distinctive clothing or signs such as the sambenito, sometimes for an entire life.[16]

Other punishments were exile, compulsory pilgrimages, fines, the galleys, life imprisonment (in fact prison for some years) and in addition the confiscation of goods and property.[186][187] The bull Ad Extirpanda determined that the houses of heretics should be completely razed to the ground.[188] Furthermore, the impact of the Inquisition's activity on the fabric of society was not limited to these penances or punishments. As under the terror of the Inquisition entire families denounced each other, they were soon reduced to misery, completed by the confiscation of property, public humiliation and ostracism. [189][187]

Even dead people could be accused, and sentenced up to forty years after the death. When inquisitors considered proven that the deceased were heretics in their lifetime, their corpses were exhumed and burned, their property confiscated and the heirs disinherited.[190][191]

Legitimation by the texts

[edit]The Inquisition always referred to biblical passages, as well as to church fathers, like Augustine of Hippo, to legitimise his actuation.

The New Testament contains some sentences that the church could interpret for dealing with heretics. The excommunication of a deviant from the faith was equivalent to handing him over to the Devil: "When you have gathered together, and my spirit with you, in the power of our Lord Jesus, hand this man over to Satan for destruction of the flesh, so that his spirit may be saved on the day of the Lord." (The Pauline letters: 1 Corinthians, B. Incest in Corinth, 5:4 and 5:5 )[192]

The sentence of Paul could also be understood in this way: he handed over to the Devil those "who have suffered shipwreck in the faith [...] so that they may be taught not to be blasphemous." (The Pastoral epistles: 1 Timothy – The first letter from Paul to Timothy—Timothy's responsibility: 1:19 and 1:20)[192]

Paul's view reflects less the idea of punishment than the idea of isolation when he says: " After a first and second warning have nothing to do with a disputatious person, since you may be sure that such a person is warped and is self-condemned as a sinner." (The Pastoral epistles : Titus – The letter from Paul to Titus—3:10 and 3:11)[192]

In the Gospel of John, Jesus tells the apostates in a parable: "I am the vine, you are the branches. Whoever remains in me, and I in that person, bears fruit in plenty; for apart from me you can do nothing. Anyone who does not remain in me is thrown away like a branch and withers. These branches are collected, thrown on the fire and burnt." This parable can be interpreted as the burning of stubborn heretics at the stake. (The Gospel according to John: The true vine—15:5 and 15:6)[192]

The celebrated theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) supplied the theoretical foundation for the medieval Inquisition in his Summa theologica II 2. 11. A heretic who repents, the first time, should be allowed penance and their life safeguarded by the church from the punishment of the secular authorities (who treated pernicious and public heresy as a kind of sedition.) A subsequent lapse into heresy would show insincerity that called for excommunication, leaving them to the secular authorities who could impose the death penalty on unprotected heretics: "Accipere fidem est voluntatis, sed tenere fidem iam acceptam est necessitatis" (i.e. "The acceptance of faith is voluntary, maintaining the accepted faith is necessary. So heretics should be compelled to keep the faith.") [193][194]

Luis de Páramo, theologian and Inquisitor of then Spanish-ruled Sicily from 1584 to 1605, asserted that Jesus Christ was "the first Inquisitor under the Evangelical law" and that John the Baptist and the apostles were also inquisitors.[195]

However, another traditional stream of Catholic thought, for example championed by Erasmus, was that the Parable of the wheat and tares forebade any premature culling of heretics.

Saint Augustine (354–430) led a debate in Africa with the Donatist community, which had split from the Roman Church. In his works, he called for moderate severity or measures by secular power, including the death penalty, against heretics, however he did not consider it desirable: "Corrigi eos volumus, non necari, nec disciplinam circa eos negligi volumus, nec suppliciis quibus digni sunt exerci", meaning "We would like them to be improved, not killed; we desire the triumph of church discipline, not the death they deserve." [196]

Controversy and revision

[edit]The opening of Spanish and Roman archives over the last 50 years has caused historians to revise their understanding of the Inquisition, some to the extent of viewing previous views as "a body of legends and myths".[197] This may mean that some older historical commentary, and sources relying on them, are not reliable sources to that extent.

Opposition and resistance

[edit]In many regions and times, there was opposition to the Inquisition.

Assassinations

[edit]In some cases, heretics and other targets did not hesitate to attempt to murder the inquisitors, or destroy its voluminous archives, because they had much to lose in the face of an inquisitorial investigation: their freedom, their property, their lives.[citation needed]

The much hated Inquisitor Konrad von Marburg, who also initiated inquisition trials against nobles, was murdered in 1233 by six mounted men on an open country road on the way to Marburg.

In 1242, a Cathar group armed with axes entered the castle of the town of Avignonet (southern France) and murdered the inquisitors Guillaume Arnaud and Étienne de Saint-Thibéry.[198]

In 1252, the inquisitor Peter of Verona was killed by Cathars. Eleven months after his assassination, he was made a Catholic saint, the quickest canonization in history. As Christine Caldwell Ames writes, "Inquisition changed what it meant to be a martyr, to be holy, and to be an imitator of Christ."[199]

In 1395 near Steyr, where the inquisitor Petrus Zwicker was quartered with associates, an assassination attempt on him failed: someone had tried to set fire to the place and burn him alive.[200]

Church opposition

[edit]Opposition to Inquisition power and abuses sometimes came from within the clergy: including friars, priests and bishops.

During French Inquisition, a Franciscan friar, Bernard Délicieux, opposed the actions of the Inquisition in Languedoc. The infamous Bernard Gui presented him as the commander-in-chief of the "iniquitous army" against the Dominicans and the Inquisition. Délicieux alleged the Inquisitiors were pursuing innocent Catholics for heresy, trying to destroy their towns. [201] He stated that the methods of the inquisition would have condemned even Peter and Paul as heretics if they appeared before the inquisitors. Délicieux later became one more victim of the Inquisition for his criticism. In 1317, Pope John XXII called him and other Franciscan Spirituals to Avignon, and he was arrested, questioned, and tortured by the Inquisition. In 1319, he was found guilty and sentenced to life in prison.[202] Fragile and old, he died shortly thereafter. [203]

In Spain, several bishops contended with inquisitorial tribunals. In 1532, the Archbishop of Toledo Alonso III Fonseca had to ransom converso Juan de Vergara (Cisneros' Latin secretary) from Spanish inquisitors. Fonseca had previously rescued Ignatius of Loyola from them.[204]: 80 Far from being a monolithic institution, sometimes the tribunals threatened individuals protected by the Inquisitor-General, such as with the Inquisitor General Alonso Manrique de Lara and Erasmus.

In Portugal, Father António Vieira (1608–1697), himself a Jesuit, philosopher, writer and orator, was one of the most important opponents of the Inquisition. Arrested by the Inquisition for "heretical, reckless, ill-sounding and scandalous propositions" in October 1665, was imprisoned until December 1667.[205] Under the Inquisitorial sentence, he was forbidden to teach, write or preach.[206][207] Only perhaps Vieira's prestige, his intelligence and his support among members of the royal family saved him from greater consequences.[208] Father Vieira led an anti-inquisition movement in Rome, where he spent six years. [209] In addition to his humanitarian objections, he also had others: he realised that a mercantile middle class was being attacked that would be sorely missed in the country's economic development.[210] He delivered a report to Pope Clement X in favour of the cause of those persecuted by the Inquisition;[211] Clement X suspended the Inquisistion between 1674 and 1681.

Statistics

[edit]Beginning in the 19th century, historians have gradually compiled statistics drawn from the surviving court records, from which estimates have been calculated by adjusting the recorded number of convictions by the average rate of document loss for each time period. Gustav Henningsen and Jaime Contreras studied the records of the Spanish Inquisition, which list 44,674 cases of which 826 resulted in executions in person and 778 in effigy (i.e. a straw dummy was burned in place of the person).[212] William Monter estimated there were 1000 executions in Spain between 1530–1630 and 250 between 1630 and 1730.[213] Jean-Pierre Dedieu studied the records of Toledo's tribunal, which put 12,000 people on trial.[214] For the period prior to 1530, Henry Kamen estimated there were about 2,000 executions in all of Spain's tribunals.[215]

Italian Renaissance history professor and Inquisition expert Carlo Ginzburg had his doubts about using statistics to reach a judgment about the period. "In many cases, we don't have the evidence, the evidence has been lost," said Ginzburg.[216]

Ending of the Inquisition in the 19th and 20th centuries

[edit]By decree of Napoleon's government in 1797, the Inquisition in Venice was abolished in 1806.[217]

In Portugal, in the wake of the Liberal Revolution of 1820, the "General Extraordinary and Constituent Courts of the Portuguese Nation" abolished the Portuguese Inquisition in 1821.

The wars of independence of the former Spanish colonies in the Americas concluded with the abolition of the Inquisition in every quarter of Hispanic America between 1813 and 1825.

The last execution of the Inquisition was in Spain in 1826.[218] This was the execution by garroting of the Catalan school teacher Gaietà Ripoll for purportedly teaching Deism in his school.[218] In Spain the practices of the Inquisition were finally outlawed in 1834.[219]

In Italy, the restoration of the Pope as the ruler of the Papal States in 1814 brought back the Inquisition to the Papal States. It remained active there until the late-19th century, notably in the well-publicised Mortara affair (1858–1870).

In 1542, a putative governing institution, the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Roman and Universal Inquisition was created. This office survived as part of the Roman Curia, although it underwent a series of name changes. In 1908, it was renamed the Supreme Sacred Congregation of the Holy Office. In 1965, it became the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.[220] In 2022, this office was renamed the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, as retained to the present day.

See also

[edit]- Auto-da-fé

- Black Legend (Spain)

- Black Legend of the Spanish Inquisition

- Cathars

- List of people executed in the Papal States

- Witch-cult hypothesis

- Witch trials in the early modern period

- Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith

- Historical revision of the Inquisition

- Marian Persecutions

Documents and works

[edit]Notable inquisitors

[edit]Notable cases

[edit]- Galileo affair

- Execution of Giordano Bruno

- Trial of Joan of Arc

- Edgardo Mortara

- Basque witch trials

- Caterina Tarongí

- Rosa Egipcíaca

Repentance

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". legacy.fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 20 March 2016. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Peters, Edwards. "Inquisition", p. 67.

- ^ a b c Lea (1887a), Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded.

- ^ Bishop, Jordan (24 April 2006). "Aquinas on Torture". New Blackfriars. 87 (1009): 229–237. doi:10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00142.x. ISSN 0028-4289.

- ^ a b Lempinen, Edward (20 July 2022). "The tortures of the Spanish Inquisition hold dark lessons for our time". Berkeley News.

- ^ Peters, Edward. "Inquisition", p. 54.

- ^ Murphy, Cullen (2012). God's Jury. New York: Mariner Books – Houghton, Mifflin, Harcourt. p. 150.

- ^ Iarocci, Michael P. (1 March 2006). Properties of Modernity. Vanderbilt University Press. p. 218. ISBN 0-8265-1522-3.

- ^ Saraiva (2001), p. 69-70.

- ^ a b Peters (1989), pp. 12–13.

- ^ a b c d Kelly, Henry Ansgar (1989). "Inquisition and the Prosecution of Heresy: Misconceptions and Abuses". Church History. 58 (4): 439–451. doi:10.2307/3168207. ISSN 0009-6407. JSTOR 3168207.

- ^ "Internet History Sourcebooks Project". Fordham.edu. Archived from the original on 14 August 2014. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Salomon, H. P. and Sassoon, I. S. D., and Saraiva, Antonio José. The Marrano Factory. The Portuguese Inquisition and Its New Christians, 1536–1765 (Brill, 2001), Introduction pp. XXX.

- ^ Peters writes: "When faced with a convicted heretic who refused to recant, or who relapsed into heresy, the inquisitors were to turn him over to the temporal authorities – the "secular arm" – for animadversio debita, the punishment decreed by local law, usually burning to death." (Peters, Edwards. "Inquisition", p. 67.)

- ^ Lea (1887a, Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded): "Obstinate heretics, refusing to abjure and return to the Church with due penance, and those who after abjuration relapsed, were to be abandoned to the secular arm for fitting punishment."

- ^ a b Kirsch (2008), p. 85.

- ^ Saraiva (2001), p. 109.

- ^ Haliczer, Stephen (1990). Inquisition and Society in the Kingdom of Valencia, 1478–1834. University of California Press. pp. 83–85.

- ^ Sullivan 2011, p. 169.

- ^ Directorium Inquisitorum, edition of 1578, Book 3, pg. 137, column 1. Online in the Cornell University Collection; retrieved 2008-05-16.

- ^ Lea (1887a, Chapter VII. The Inquisition Founded): "The judicial use of torture was as yet happily unknown..."

- ^ Foxe, John. "Chapter monkey" (PDF). Foxe's Book of Martyrs. Archived from the original (PDF) on 26 November 2012. Retrieved 31 August 2010.

- ^ Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Ava Rojas Company. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

... in this period the more influential ecclesiastical authorities declared that the death penalty was contrary to the spirit of the Gospel, and they themselves opposed its execution. For centuries this was the ecclesiastical attitude both in theory and in practice. Thus, in keeping with the civil law, some Manichæans were executed at Ravenna in 556. On the other hand, Elipandus of Toledo and Felix of Urgel, the chiefs of Adoptionism and Predestinationism, were condemned by councils, but were otherwise left unmolested. We may note, however, that the monk Gothescalch, after the condemnation of his false doctrine that Christ had not died for all mankind, was by the Synods of Mainz in 848 and Quiercy in 849 sentenced to flogging and imprisonment, punishments then common in monasteries for various infractions of the rule.

- ^ Blötzer, J. (1910). "Inquisition". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Robert Appleton Company. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

[...] the occasional executions of heretics during this period must be ascribed partly to the arbitrary action of individual rulers, partly to the fanatic outbreaks of the overzealous populace, and in no wise to ecclesiastical law or the ecclesiastical authorities.

- ^ Hughes, Philip (1979). History of the Church Volume 2: The Church In The World The Church Created: Augustine To Aquinas. A&C Black. pp.27–28, ISBN 978-0-7220-7982-9

- ^ Peters (1980), p. 170-173.

- ^ Théry, Julien; Gilli, Patrick (2010). "" Expérience italienne et norme inquisitoriale ", chap.11(in Le gouvernement pontifical et l'Italie des villes au temps de la théocratie (fin XIIe-mi-XIVe siècle)". Academia (in French). Presses universitaires de la Méditerranée. pp. 547–592. Retrieved 6 May 2024.

- ^ "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Inquisition". Newadvent.org. Archived from the original on 26 October 2007. Retrieved 13 October 2017.

- ^ Bishop, Jordan (2006). "Aquinas on Torture". New Blackfriars. 87 (1009): 229–237. doi:10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00142.x.

- ^ Larissa Tracy, Torture and Brutality in Medieval Literature: Negotiations of National Identity, (Boydell and Brewer Ltd, 2012), 22; "In 1252 Innocent IV licensed the use of torture to obtain evidence from suspects, and by 1256 inquisitors were allowed to absolve each other if they used instruments of torture themselves, rather than relying on lay agents for the purpose...".

- ^ Pegg, Mark G. (2001). The Corruption of Angels – The great Inquisition of 1245–1246. Princeton University Press. p. 32.

- ^ "Appendix 2: List of Inquisitors-General". libro.uca.edu. Retrieved 13 May 2024.

- ^ Kras, Paweł. Ad abolendam diversarum haeresium pravitatem. System inkwizycyjny w średniowiecznej Europie. KUL 2006, p. 411. Del Col, Andrea. Inquisizione in Italia, p. 3.

- ^ Lansing, Carol. Power and Purity: Cathar Heresy in Medieval Italy, 2001, p. 138.

- ^ Prudlo, Donald. The martyred inquisitor. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008. p. 42.

- ^ Del Col, p. 96–98. Already in 1233 in Verona, 60 Cathars were burnt on the order of the Dominican Giovanni da Vicenza, but formally he issued this sentence as the podesta of this city, and not the inquisitor, which he became only in 1247. Cf. Lea (1887b, pp. 204, 206).

- ^ a b Paweł Kras: Ad abolendam diversarum haeresium pravitatem. System inkwizycyjny w średniowiecznej Europie, KUL 2006, p. 413.

- ^ Lea, vol. II, pp. 264, 267.

- ^ Tavuzzi, Michael M. Renaissance inquisitors: Dominican inquisitors and inquisitorial districts in Northern Italy, 1474–1527. Leiden & Boston: Brill (2007). p. 197, 253–258; Del Col, p. 196–211.

- ^ Behringer, W. Witches and Witch-Hunts: A Global History. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press Ltd (2004). p. 130

- ^ Lea, vol. III, p. 515; cf. Tavuzzi, p. 150–151, 184–185.

- ^ Tavuzzi, p. 188–192; Del Col, p. 199–200, 204–209.

- ^ Sumption (1978), pp. 230–232.

- ^ Costen (1997), p. 173.

- ^ The characteristics of the activities of the Inquisition in France in the 13th–15th centuries are presented by Lea (1887b, pp. 113–161).

- ^ Robert's activities are described by Lea (1887b, pp. 114–116); P. Kras, Ad abolendam..., pp. 163–165; and M. Lambert, The Cathars, pp. 122–125.

- ^ Richard Kieckhefer: Magia w średniowieczu, Cracovia 2001, págs. 278–279.

- ^ P. Kras, Ad abolendam..., p.412.

- ^ Lea (1887b), p. 30.

- ^ Wakefield, s. 184; M. Barber, Katarzy, p. 126.

- ^ M.D. Costen, The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, Manchester University Press, 1997, p. 170.

- ^ P. Kras: Ad abolendam..., p. 412–413.

- ^ Malcolm Lambert: Średniowieczne herezje, Wyd. Marabut Gdańsk-Warszawa 2002, p. 195–196.

- ^ Lea (1887a), p. 485.

- ^ M.D. Costen: The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, Manchester University Press, 1997, p. 171

- ^ Wakefield, p. 184.

- ^ M.D. Costen: The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade, Manchester University Press, 1997, p. 171.

- ^ List of judgments from: James Given: Inquisition and Medieval Society, Cornell University Press, 2001, s. 69–70.

- ^ P. Kras: Ad abolendam..., p. 413.

- ^ Jean Guiraud: Medieval Inquisition, Kessinger Publishing 2003, p. 137.

- ^ Marx: L'inquisition en Dauphine, 1914, p. 128 note. 1, pp. 134–135, and Tanon, pp. 105–106. Jean Paul Perrin: History of the ancient Christians inhabiting the valleys of the Alps, Philadelphia 1847, p. 64, gives figures of over 150 convicts from the Valpute valley and 80 from the other two, but cites the same document as Marx and Tanon.

- ^ Raymond Mentzer: Heresy Proceedings in Languedoc, 1500–1560, American Philosophical Society, 2007, s. 122.

- ^ William E. Burns (red.): Witch hunts in Europe and America: an encyclopedia, Greenwood Publishing Group 2003, s. 104.

- ^ Andrea Del Col: Inquisizione in Italia, p. 434, 780.

- ^ Lea (1887b), pp. 332, 346.

- ^ P. Kras: Ad abolendam..., s. 414.

- ^ Lea (1887b), p. 375.

- ^ "Urkundliche Mittheilungen über die Beghinen- und Begharden-Häuser zu Rostock". mvdok.lbmv.de. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- ^ Lea (1887b), p. 390.

- ^ The description of these persecutions is published by: Lea (1887b, pp. 395–400); and R. Kieckhefer: Repression of heresy, p. 55.

- ^ Manfred Wilde, Die Zauberei- und Hexenprozesse in Kursachsen, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2003, p. 100–101; K.B. Springer: Dominican Inquisition in the archidiocese of Mainz 1348–1520, w: Praedicatores, Inquisitores, Vol. 1: The Dominicans and the Medieval Inquisition. Acts of the 1st International Seminar on the Dominicans and the Inquisition, 23–25 February 2002, red. Arturo Bernal Palacios, Rzym 2004, p. 378–379; R. Kieckhefer: Repression of heresy, p. 96–97. Lea (1887b, p. 408) mentions at least 135 executions in 1414 and another 300 two years later, but most likely the sources he cites speak of the same repressive action, with different dates (Springer: p. 378 note 276; Kieckhefer: p. 378, note 276; : pp. 97 and 147).

- ^ K.B. Springer: Dominican Inquisition in the archidiocese of Mainz 1348–1520, w: Praedicatores, Inquisitores, Vol. 1: The Dominicans and the Medieval Inquisition. Acts of the 1st International Seminar on the Dominicans and the Inquisition, 23–25 February 2002, red. Arturo Bernal Palacios, Rzym 2004, p. 381. The mass executions of flagellants in Thuringia in 1454 were the work of secular authorities, see Kieckhefer, Repression of heresy, p. 147; Manfred Wilde, Die Zauberei- und Hexenprozesse in Kursachsen, Böhlau Verlag Köln Weimar, 2003, p. 106–107.

- ^ Institoris, Heinrich; Sprenger, Jakob; Sprenger, James (2000). The Malleus Maleficarum of Heinrich Kramer and James Sprenger. Book Tree. ISBN 978-1-58509-098-3.

- ^ cf. Lea (1887c, p. 540)

- ^ BBKL: Jacob von Hoogstraaten