Mark Satin

Mark Satin | |

|---|---|

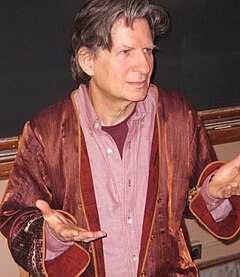

Satin talking about "life and political ideologies" in 2011 | |

| Born | Mark Ivor Satin November 16, 1946 |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | University of British Columbia (BA) New York University (JD) |

| Occupation(s) | Political theorist Writer Newsletter publisher |

| Years active | 1967–present |

| Notable work | Radical Middle New Age Politics Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada |

| Website | www |

Mark Ivor Satin (born November 16, 1946) is an American political theorist, writer, and newsletter publisher. He is best known for contributing to the development and dissemination of three political perspectives – neopacifism in the 1960s, New Age politics in the 1970s and 1980s, and radical centrism in the 1990s and 2000s. Satin's work is sometimes seen as building toward a new political ideology, and then it is often labeled "transformational",[1] "post-liberal",[2] or "post-Marxist".[3] One historian calls Satin's writing "post-hip".[4]

After emigrating to Canada at the age of 20 to avoid serving in the Vietnam War, Satin co-founded the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme, which helped bring American war resisters to Canada. He also wrote the Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada (1968), which sold nearly 100,000 copies.[5] After a period that author Marilyn Ferguson describes as Satin's "anti-ambition experiment",[6] Satin wrote New Age Politics (1978), which identifies an emergent "third force" in North America pursuing such goals as simple living, decentralism, and global responsibility. Satin spread his ideas by co-founding an American political organization, the New World Alliance, and by publishing an international political newsletter, New Options. He also co-drafted the foundational statement of the U.S. Green Party, "Ten Key Values".

Following a period of political disillusion, spent mainly in law school and practicing business law,[7] Satin launched a new political newsletter and wrote a book, Radical Middle (2004). Both projects criticized political partisanship and sought to promote mutual learning and innovative policy syntheses across social and cultural divides. In an interview, Satin contrasts the old radical slogan "Dare to struggle, dare to win"[nb 1] with his radical-middle version, "Dare to synthesize, dare to take it all in".[9]

Satin has been described as "colorful"[10] and "intense",[11] and all his initiatives have been controversial. Bringing war resisters to Canada was opposed by many in the anti-Vietnam War movement. New Age Politics was not welcomed by many on the traditional left or right, and Radical Middle dismayed an even broader segment of the American political community. Even Satin's personal life has generated controversy. At age 76, Satin wrote a book seeking to draw lessons from his political and personal journey, Up From Socialism: My 60-Year Search for a Healing New Radical Politics (2023).

Early years

[edit]Many mid-1960s American radicals came from small cities in the Midwest and Southwest,[12] as did Satin: he grew up in Moorhead, Minnesota,[13] and Wichita Falls, Texas.[14] His father, who saw combat in World War II,[15] was a college professor and author of a Cold War-era textbook on Western civilization.[16] His mother was a homemaker.[17]

As a youth, Satin was restless and rebellious,[18][19] and his behavior did not change after leaving for university.[20][21] In early 1965, at age 18, he dropped out of the University of Illinois[22] to work with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee in Holly Springs, Mississippi.[7] Later that year, he was told to leave Midwestern State University, in Texas, for refusing to sign a loyalty oath to the United States Constitution.[nb 2][nb 3] In 1966 he became president of a Students for a Democratic Society chapter at the State University of New York at Binghamton, and helped recruit nearly 20% of the student body to join.[7] One term later he dropped out,[26] then emigrated to Canada to avoid serving in the Vietnam War.[23]

Just before Satin left for Canada, his father told him he was trying to destroy himself.[15] His mother told the Ladies' Home Journal she could not condone her son's actions.[20] Satin says he arrived in Canada feeling bewildered and unsupported.[27] According to press accounts, many Vietnam War resisters arrived feeling much the same way.[28][29]

Neopacifism, 1960s

[edit]Toronto Anti-Draft Programme

[edit]As 1967 began, many American pacifists and radicals did not look favorably on emigration to Canada as a means of resisting the Vietnam War.[30] For some this reflected a core conviction that effective war resistance requires self-sacrifice.[31][32] For others it was a matter of strategy – emigration was said to be less useful than going to jail[33] or deserting the military,[34] or was said to abet the war by siphoning off the opposition.[30] At first, Students for a Democratic Society and many Quaker draft counselors opposed promoting the Canadian alternative,[35] and Canada's largest counseling group, the Anti-Draft Programme of the Student Union for Peace Action (SUPA)[36] – whose board consisted largely of Quakers and radicals[36] – was sympathetic to such calls for prudence.[37][38] In January 1967 its spokesman warned an American audience that immigration was difficult and that the Programme was not willing to act as "baby sitters" for Americans after they arrived. He added that he was tired of talking to the press.[39]

When Mark Satin was hired as director of the Programme in April 1967, he attempted to change its culture.[38] He also tried to change the attitude of the war resistance movement toward emigration.[40] His efforts continued after SUPA collapsed and he co-founded the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme, with largely the same board of directors, in October 1967.[41] Instead of praising self-sacrifice, he emphasized the importance of self-preservation and self-development to social change.[42] Rather than sympathizing with pacifists' and radicals' strategic concerns, he rebutted them, telling The New York Times that massive emigration of draft-age Americans could help end the war,[43] and telling another reporter that going to jail was bad public relations.[20]

Where the Programme once publicized the difficulties of immigration, Satin emphasized the competence of his draft counseling operation,[14][23] and even told of giving cash to immigrants who were without funds.[43][nb 4] Instead of refusing to "baby sit" Americans after they arrived, Satin made post-emigration assistance a top priority. The office soon sported comfortable furniture, a hot plate, and free food;[23] within a few months, 200 Torontonians had opened their homes to war resisters[43] and a job-finding service had been established.[43][45] Finally, rather than expressing indifference to reporters, Satin courted them, and many responded,[35] beginning with a May 1967 article in The New York Times Magazine that included a large picture of Satin counseling Vietnam War resisters in the refurbished office.[13] Some of the publicity focused on Satin as much as on his cause.[14][23] According to historian Pierre Berton, Satin was so visible that he became the unofficial spokesman for war resisters in Canada.[33]

Satin defined himself as a neopacifist or quasi-pacifist[nb 5] – flexible, media-savvy, and entrepreneurial.[38][47] He told one journalist he might have fought against Hitler.[13] He was not necessarily opposed to the draft, telling reporters he would support it for a defensive army[28][48] or to help eliminate poverty, illiteracy, and racial discrimination.[28][49] He avoided the intellectual framework of traditional pacifism and socialism. Sometimes he spoke with emotion, as when he described the United States to The New York Times Magazine as "[t]hat godawful sick, foul country; could anything be worse?"[13] Sometimes he spoke poetically, as when he told author Jules Witcover, "It's colder here, but you feel warm because you know you're not trying to kill people."[50] Instead of identifying with older pacifists, he identified with a 17-year-old character from the pen of J. D. Salinger: "I was Holden Caulfield", he said in 2008, "just standing and catching in the rye."[15]

The results of Satin's approach were noticeable: the Programme went from averaging fewer than three visitors, letters, and phone calls per day just before he arrived,[39] to averaging 50 per day nine months later.[15][nb 6] In addition, the American anti-war movement became more accepting of emigration to Canada – for example, author Myra MacPherson reports that Satin's Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada could be obtained at every draft counseling office in the U.S.[51] However, Satin's approach was distressing to the traditional pacifists and socialists on the Programme's board. The board clashed with Satin over at least 10 political, strategic, and performance issues.[41] The most intractable may have been over the extent of the publicity.[15] There were also concerns about Satin's personal issues; for example, one war resister claims to have heard him say, "Anonymity would kill me".[52] In May 1968, the board finally fired him.[41][53]

Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada

[edit]

Before Satin was fired, he conceived and wrote, and edited guest chapters for, the Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada, published in January 1968[54] by the House of Anansi Press in partnership with the Toronto Anti-Draft Programme.[41] The Programme had issued brochures on emigration before[36] – including a 12-page version under Satin's watch[20] – but the Manual was different, a comprehensive, 45,000-word book, and it quickly turned into an "underground bestseller".[51] Many years later, Toronto newspapers reported that nearly 100,000 copies of the Manual had been sold.[5][55][nb 7] One journalist calls it the "first entirely Canadian-published bestseller in the United States".[54]

The Programme was initially hesitant about producing the Manual,[41] which promised to draw even more war resisters and publicity to it. "The [board] didn't even want me to write it", Satin says. "I wrote it at night, in the SUPA office, three or four nights a week after counseling guys and gals 8 to 10 hours a day – pounded it out in several drafts over several months on SUPA's ancient Underwood typewriter."[41] When it finally appeared, some leading periodicals helped put it on the map.[54] For example, The New York Review of Books called it "useful",[58] and The New York Times said it contains advice about everything from how to qualify as an immigrant to jobs, housing, schools, politics, culture, and even the snow.[43] After the war, sociologist John Hagan found that more than a third of young American emigrants to Canada had read the Manual while still in the United States, and nearly another quarter obtained it after they arrived.[10]

The Manual reflected Satin's neopacifist politics. Commentators routinely characterized it as caustic,[59] responsible,[33] and supportive.[54] The first part of the Manual, on emigration, suggests that self-preservation is more important than sacrifice to a dubious cause.[42] The second half, on Canada, spotlights opportunities for self-development and social innovation.[60] According to Canadian social historian David Churchill, the Manual helped some Canadians begin to see Toronto as socially inclusive, politically progressive, and counter-cultural.[36]

"Draft resisters have had and should continue to have only normal difficulties immigrating [to Canada]. Probably any young American can get in if he is really determined, though all will need adequate information. ... The toughest problem a draft resister faces is not how to immigrate but whether he really wants to. And only you can answer that. For yourself. That's what Nuremberg was all about."

– Mark Satin in 1968, on military service and the individual conscience.[61]

Inevitably, the Manual became a lightning rod for controversy.[62] Some observers took issue with its perspective on Canada;[59] most notably, The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature criticizes its "condescending tone" in describing Canada's resources.[63] Elements in the U.S. and Canadian governments may have been upset by the Manual. According to journalist Lynn Coady, the FBI and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) attempted to wiretap the House of Anansi Press's offices.[64] In addition, Anansi co-founder Dave Godfrey is convinced a 10-day government audit of the press was generated by FBI–RCMP concerns.[41] Many people did not want the Programme to encourage draft-eligible Americans to emigrate to Canada,[54][65] and Satin routinely denied that the Manual encouraged emigration.[66][67] But few observers believed him, then or later. The first sentence of an article in The New York Times from 1968 describes the Manual as "a major bid to encourage Americans to evade military conscription".[43] Canadian essayist Robert Fulford remembers the Manual as offering an enthusiastic welcome to draft dodgers.[68] Even a House of Anansi Press anthology from 2007 concedes that the Manual is "coyly titled".[64]

Satin was fired from the Programme soon after the appearance of the second edition of the Manual, which had a print run of 20,000.[41] His name was removed from the title page of most subsequent editions.[69] According to a study of the Manual by critic Joseph Jones in Canadian Notes & Queries, a literary journal, some later editions experienced a falloff in quality.[41] Nevertheless, Jones says the Manual stands as an icon of its age.[41] It made significant appearances in at least five 20th-century novels, including John Irving's A Prayer for Owen Meany,[41] and it continues to be pored over by journalists,[70] historians,[71][72] social scientists,[10] creative writers,[73] social movement strategists,[74][75] and graduate students.[76] In 2017 the Manual was re-issued as a Canadian "classic" by the original publisher, with an introduction by Canadian historian James Laxer and a politically charged afterword by Satin, then in his 70th year.[56][77]

Confessions of a Young Exile

[edit]

Until the 1990s, literary critic William Zinsser says, memoir writers tended to conceal their most personal and embarrassing memories.[78] In the 1970s Satin wrote a book revealing many such memories as a neopacifist activist during the years 1964–66, Confessions of a Young Exile, published by Gage, a Toronto publishing house soon to merge with Macmillan of Canada.[79] Confessions is "a remarkable exercise in self-exposure", playwright John Lazarus says in a review. "The insights into the hero's motives and fears are so honest, and so mortifyingly true, that it soon becomes evident that the [naive] tone is deliberate."[80]

To some reviewers, Satin appears to have had a political goal – encouraging activists to establish common ground with ordinary North Americans on the basis of their shared confusion and humanity. For example, Jackie Hooper, writing in The Province, argues that the purity of motives projected by many pacifist activists is unconvincing, and recommends Satin's more complex view: "Satin's emigration wasn't dictated totally by his idealism. More often than not, he talked himself into radical positions ... as a result of trying to impress his peers or his girlfriend, or rebelling against middle-class parental authority".[81] Roy MacSkimming, book editor of the Toronto Star, says Satin portrayed himself as "idealistic" but also troubled and uncertain, wanting to fit in yet also longing to be unique.[82]

Some reviewers were unenthusiastic. For example, Dennis Duffy, writing in The Globe and Mail, describes Satin's memoir as a "story about a young man who doesn't grow up".[83] In addition, Satin's publisher began having reservations about him. Many years later, the Toronto Star reported that the publisher decided not to let Satin do any publicity for the book, because of his potentially offensive views.[15]

In the 21st century, Confessions was discussed at length by literary critics Rachel Adams in the Yale Journal of Criticism[84] and Robert McGill in his book War Is Here.[85] Both had been drawn to Satin's text because of their interest in the figure of the "draft dodger" in literature,[86][87] and both depict Satin's journey from Moorhead to Canada as politically complex and sexually charged.[84][85]

New Age politics, 1970s – 1980s

[edit]New Age Politics, the book

[edit]As the 1970s began, the New Left faded away,[88] and many movements arose in its wake – among them the feminist, men's liberation, spiritual, human potential, ecology, appropriate technology, intentional community, and holistic health movements.[89][90] After graduating from the University of British Columbia in 1972,[11] Satin immersed himself in all these movements, either directly[91] or as a reporter for Canada's underground press.[6] He also took up residence in a free-love commune.[15] "One fierce winter's day", he says, "... it dawned on me that the ideas and energies from the various 'fringe' movements [were] beginning to generate a coherent new politics. But I looked in vain for the people and groups that were expressing that new politics (instead of merely bits and pieces of it)".[92] Satin set out to write a book that would express the new politics in all its dimensions.[92] He wrote, designed, typeset, and printed the first edition of New Age Politics himself, in 1976.[93] A 240-page edition was published by Vancouver's Whitecap Books in 1978,[94] and a 349-page edition by Dell Publishing Company in New York in 1979.[nb 8] It is now widely regarded as the "first",[95][96] "most ambitious",[97] or "most adequate"[98] attempt to offer a systemic overview of the new post-socialist politics arising in the wake of the New Left. Some academics say it offers a new ideology.[3][99]

At the heart of New Age Politics is a critique of the consciousness we all supposedly share, a "six-sided prison" that has kept us all trapped for hundreds of years. The six sides of the "prison" are said to be: patriarchal attitudes, egocentricity, scientific single vision, the bureaucratic mentality, nationalism (xenophobia), and the "big city outlook" (fear of nature). Since consciousness, according to Satin, ultimately determines our institutions, prison consciousness is said to be ultimately responsible for "monolithic" institutions that offer us little in the way of freedom of choice or connection with others. Some representative monolithic institutions are: bureaucratic government, automobile-centered transportation systems, attorney-centered law, doctor-centered health care, and church-centered spirituality.[101]

To explain how to break free of the prison and its institutions, Satin develops a "psychocultural" class analysis that reveals the existence of "life-", "thing-", and "death-oriented" classes. According to Satin, life-oriented individuals constitute an emerging "third force" in post-industrial nations. The third force is generating a "prison-free" consciousness consisting of androgynous attitudes, spirituality, multiple perspectives, a cooperative mentality, local-and-global identities, and an ecological outlook. To transform prison society, Satin argues, the third force is going to have to launch an "evolutionary movement" to replace – or at least supplement – monolithic institutions with life-affirming, "biolithic" ones. Some representative biolithic institutions are: deliberative democracy as an alternative to bureaucratic government, bicycles and mass transit as an alternative to the private automobile, and mediation as an alternative to attorney-centered law. According to Satin, the third force will not have to overthrow capitalism, since Western civilization – not capitalism – is said to be responsible for the prison.[nb 9] But the third force will want to foster a prison-free New Age capitalism through intelligent regulation and elimination of all subsidies.[101]

"Gradually reorganize the armed forces into a multipurpose civilian-defense-and-social-service organization that would train us in the arts of nonviolent and 'territorial' – nonviolent plus guerrilla – defense. [And] re-establish the civilian draft. Without a civilian army the powerful life-rejecting people in this country may never peacefully relinquish their power; and without a citizenry professionally trained in the arts of nonviolent and territorial defense, we may never dare to put an end to the arms race."

– Mark Satin in 1979, on military service and New Age ideals.[102]

The reaction to New Age Politics was, and continues to be, highly polarized. Many of the movements Satin drew upon to construct his synthesis received it favorably,[103] though some took exception to the title.[104] Some maverick liberals and libertarians are drawn to the book.[105][106] It was eventually published in Sweden[107][nb 10] and Germany,[109][nb 11] and European New Age political thinkers came to see it as a precursor of their own work.[110][nb 12] Others see it as proto-Green.[99][113][nb 13] Ever since its first appearance, though, and continuing into the 21st century, New Age Politics has been a target of criticism for two groups in the United States: conservative Christians and left-wing intellectuals.

Among conservative Christians, there are cultural, political, and moral objections. Attorney Constance Cumbey warns that the book can be "seductive" to those who lack an adequate Biblical education.[116] Theologians Tim LaHaye and Ron Rhodes are convinced Satin wants a centralized and coercive world government.[117][118] Moral philosopher Douglas Groothuis says Satin's vision is unsound because it lacks an absolute standard of good and evil.[119] Among left-leaning academics, criticism focuses on Satin's theoretical underpinnings. Political scientist Michael Cummings takes issue with the idea that consciousness is ultimately determining.[120] Science-and-society professor David Hess rejects the idea that economic class analysis should give way to psychocultural class analysis.[121] A lengthy, systemic critique of New Age Politics, by communication studies professor Dana L. Cloud, accuses it of employing a "therapeutic rhetoric[] generated to console activists after the failure of post-1968 revolutionary movements and to legitimate participation in liberal politics".[122][nb 14]

Organizing the New World Alliance

[edit]

After U.S. President Jimmy Carter pardoned[nb 15] Vietnam War resisters in 1977, Satin began giving talks on New Age Politics in the United States.[6] His first talk received a standing ovation, and he wept.[92] Every talk seemed to lead to two or three more, and "the response at New Age gatherings, community events, fairs, bookstores, living rooms, and college campuses" kept Satin going for two years.[7] By the second year he began laying the groundwork for the New World Alliance, a national political organization based in Washington, D.C.[6] "I went systematically to 24 cities and regions from coast to coast", he told the authors of the book Networking.[125] "I stopped when I found 500 [accomplished] people who said they'd answer a questionnaire ... on what a New Age-oriented political organization should be like – what its politics should be, what its projects should be, and how its first directors should be chosen.".[125][nb 16]

The New World Alliance convened its first "governing council" meeting in New York City in 1979.[125] The 39-member council was chosen by the questionnaire-answerers themselves, out of 89 who volunteered to be on the ballot.[125] Political scientist Arthur Stein describes the council as an eclectic collection of educators, feminists, businesspeople, futurists, think-tank fellows, and activists.[129] One of the council's announced goals was to break down the division between left and right.[129][130] Another was to help facilitate a thorough transformation of society.[130][131] Satin was named staff member of the Alliance.[6]

Expectations ran high among supporters of a post-liberal, post-Marxist politics,[132] and the governing council did initiate several projects. For example, a series of "Political Awareness Seminars" attempted to help participants understand and learn to work with their political opponents.[133] In addition, a "Transformation Platform" attempted to synthesize left- and right-wing approaches to dozens of public policy issues.[129] But within three years the Alliance fell apart, unable to establish stable chapters in any major cities.[134] Author Jerome Clark suggests the cause was the Alliance's commitment to consensus-building in all its groups and projects; within months, he notes, one member was complaining that the Alliance had turned into a "diddler's cult".[134] Another explanation focuses on the failure – or inability – of the hyper-democratic questionnaire process to select an appropriate governing council.[134]

Satin was devastated by the decline of the Alliance, and engaged in unhappy bouts of public criticism and self-criticism.[129] "We would rather be good than do good", he told editor Kevin Kelly. "We would rather be pure than mature. We are the Beautiful Losers."[135] As time went on, though, the Alliance came to be regarded positively by many observers. For example, author Corinne McLaughlin sees it as one of the first groups to offer an agenda for the new transformational politics.[136] In an academic text, political scientist Stephen Woolpert acknowledges it as a precursor of North American Green parties.[137]

New Options Newsletter

[edit]After four or five New World Alliance governing council meetings, Satin became tired of what he saw as empty rhetoric, and decided to do something practical – start a political newsletter.[6] He raised $91,000[nb 17] to launch the venture, from 517 people he had met on his travels,[6] and within a few years had built it into what think-tank scholar George Weigel described as "one of the hottest political newsletters in Washington[, D.C.]. ... [It] has gotten a fair amount of [national] attention, and perhaps even some influence, because it self-consciously styles itself 'post-liberal'."[139] Satin published 75 issues of New Options from 1984 to 1992, virtually half a million words.[140] He wrote nearly all the articles.[2] In 1989 New Options received Utne Reader's first "Alternative Press Award for General Excellence: Best Publication from 10,000 to 30,000 Circulation".[141] In 1990 The Washington Post identified New Options as one of 10 periodicals spearheading "The Ideology Shuffle".[142] Twenty-five of its articles were published as a book by a university press.[143]

Satin wanted New Options to make the visionary perspective of New Age Politics seem pragmatic and realizable.[146] He also wanted New Options to spread the New Age political ideology more effectively than the New World Alliance had done.[147] To those ends, he challenged traditional views across the political spectrum,[148] and he expanded the scope of politics to include subjects like love and relationships.[148] In her book Do You Believe in Magic?, culture critic Annie Gottlieb says New Options offered:

an explosive short course in political possibility. ... What are the best books and groups in the consumer empowerment (not "protection") and neighborhood self-reliance movements? Who is working on practical, compassionate, populist alternatives to the welfare state and the big-business state? What is the best way to cut the budget deficit? What can we learn from the Sri Lankan Sarvodaya (local self-help) and Polish Solidarity movements? Each issue presents ideas, names and addresses, and a crossfire of reader debate.[146]

"I think the reason New Options works is it has a particular tone", Satin told one reporter. "It's as idealistic as many of us were in the 1960s, but ... without the childishness".[2]

New Options owed its rise to more than just content and tone, however. Positioning was also a factor. The New Age political movement was cresting in the 1980s,[149] and it needed a political periodical. Satin's book New Age Politics had helped define the movement,[134] and the New Options advisory board – a collection of prominent post-liberal thinkers – gave the newsletter further credibility. At the outset it included Lester R. Brown, Ernest Callenbach, Fritjof Capra, Vincent Harding, Willis Harman, Hazel Henderson, Petra Kelly, Amory Lovins, Joanna Macy, Robin Morgan, John Naisbitt, Jeremy Rifkin, Carl Rogers, Theodore Roszak, Kirkpatrick Sale, Charlene Spretnak, and Robert Theobald,[150] and over the years it added such figures as Herman Daly, Marilyn Ferguson, Jane Jacobs, Winona LaDuke, and Robert Rodale.[151]

New Options did not succeed in all quarters. Jules Feiffer, for example, often seen as being on the liberal-left, called it "irritating" and "neo-yuppie".[152] Jason McQuinn, often seen as a radical, objected to what he perceived as its relentless American optimism.[153] George Weigel, often seen as a conservative, said it consisted largely of a cleverly repackaged leftism.[139] Satin himself turned out to be one of the newsletter's critics. "I could have edited New Options forever", he wrote in 2004. "But, increasingly, I was becoming dissatisfied with my hyper-idealistic politics".[7] His experiences in the U.S. Green politics movement contributed to that dissatisfaction.[154][155]

"Ten Key Values" of the U.S. Green Party

[edit]

By the mid-1980s, Green parties were making inroads all over the world.[156][157] A slogan of the West German Greens was, "We are neither left nor right; we are in front".[158] Some observers, notably British Green Party liaison Sara Parkin, saw the New World Alliance and New Options Newsletter as Green entities.[131] Others saw the early Greens as one expression of New Age politics.[134][159] In 1984, Satin was invited to the founding meeting of the U.S. Green politics movement,[160] and he became a founding member.[161] The meeting chose him, along with political theorist Charlene Spretnak, to draft its foundational political statement, "Ten Key Values".[158][162] Some accounts recognize futurist and activist Eleanor LeCain as a co-equal drafter.[158][163] The drafters drew on suggestions recorded on a flip chart during a marathon plenary brainstorming session, as well as on suggestions received by Satin and Spretnak during the meeting and for many weeks afterward.[158][162]

The original "Ten Key Values" statement was approved by the Greens' national steering committee[163] and released in late 1984. The values in the original statement are: Ecological Wisdom, Grassroots Democracy, Personal and Social Responsibility, Nonviolence, Decentralization, Community-based Economics, Postpatriarchal Values, Respect for Diversity, Global Responsibility, and Future Focus.[162][164][165] One unusual aspect, say many observers, is the way the values are described; instead of declaratory statements full of "shoulds" and "musts", each value is followed by a series of open-ended questions.[166][167] "That idea ... came from Mark Satin", Spretnak told scholar Greta Gaard in 1997.[158] Its effect, says sociologist Paul Lichterman, was to promote dialogue and creative thinking in local Green groups across the U.S.[167]

"How can we, as a society, develop effective alternatives to our current patterns of violence, at all levels, from the family and the street to nations and the world? How can we eliminate nuclear weapons from the face of the Earth without being naive about the intentions of other governments? How can we most constructively use nonviolent methods to oppose practices and policies with which we disagree ... ?"

– Original "Ten Key Values" statement, on nonviolence and Green politics.[168]

The original values statement was, and remains, controversial. U.S. Green Party co-founder John Rensenbrink credits it with helping to unify the often contentious Greens.[169] However, party co-founder Howie Hawkins sees it as just a watered-down, "spiritual", and "New Age" version of the German Greens' Four Pillars statement.[158] Greta Gaard says it fails to call for the elimination of capitalism or racism.[158] Looking back after 20 years, Green activist Brian Tokar said that "the voice of the original [values] questions is distinctly personal ... and aims to avoid fundamental conflicts with elite social and cultural norms."[170] A "modified"[166] list of the Ten Key Values became part of the U.S. Greens' political platform.[171] However, all the open-ended questions were replaced by declaratory sentences,[171] and the U.S. Greens have come to be regarded as a party of the left, rather than one seeking to be neither left nor right.[172][nb 18]

Satin himself became increasingly critical of the Greens. He gave a featured speech at the U.S. Green gathering in 1987 urging them to avoid hyper-detailed platform writing and other projects and specialize in one thing – running people for office who endorse the Ten Key Values. But the speech failed to persuade.[162] After the Green gathering in 1989, he urged them to abandon hippie-era fears of money, authority, and leadership.[174] After the 1990 gathering he complained "I've been Pure before,"[175] an allusion to his time in the New World Alliance. According to Greta Gaard, he then bid farewell to the Greens, but recognized it as a loss: "Whatever I may think of their internal battles and political prospects, the Greens are My People. Their life choices are my life choices; their failings mirror my own."[175] Within a year of voicing those words, he stopped New Options Newsletter and applied to law school.[148][176]

Radical centrist politics, 1990s – 2000s

[edit]Radical Middle Newsletter

[edit]The 1990s are remembered, by many in the West, as a time of relative prosperity and satisfaction.[177] According to some historians, visionary politics appeared to be on the decline.[178][179] However, even after Satin entered New York University School of Law in 1992, he expressed no desire to abandon his project of helping to construct a post-liberal, post-Marxist ideology.[11] He did admit to being disillusioned with his approach. "I knew my views (and I personally) would benefit from engagement with the real world of commerce and professional ambition", he wrote.[180]

After graduating in 1995, Satin worked for a Manhattan law firm focusing on complex business litigation.[15] He also wrote about financial and legal issues.[181] He did not dislike his work, but felt he was "sleepwalking" because he was not doing what he loved, writing about visionary politics.[180] With six former law school classmates,[182] he began planning a political newsletter that could accommodate all he was learning about business and law.[180] In 1998 he returned to Washington, D.C., to launch Radical Middle Newsletter.[nb 19]

As the title indicates, it sought to distance itself from New Age politics. If the term "New Age" suggests utopianism,[105] the term "radical middle" suggests, for Satin and others, keeping at least one foot firmly on the ground.[184][185] Satin attempted to embrace the promise but also the balance implied by the term.[186][187] One feature story is entitled "Tough on Terrorism, and Tough on the Causes of Terrorism".[188] Another feature story attempts to go beyond polarized positions on biotechnology.[186] Another argues that corporate activity abroad can best be seen as neither inherently moral nor inherently imperialistic, but as a "chance for mutual learning".[189] The board of advisors of Radical Middle Newsletter signaled Satin's new direction. It was politically diverse, and many of its members sought to promote dialogue or collaboration across ideological divides. By the end of 2004 it included John Avlon, Don Edward Beck, Jerry H. Bentley, Esther Dyson, Mark P. Painter, Shelley Alpern of the Social Investment Forum, James Fallows of the New America Foundation, Jane Mansbridge of the Harvard Kennedy School, John D. Marks and Susan Collin Marks of Search for Common Ground, and William Ury, co-author of Getting to Yes.[190]

Radical Middle Newsletter proved controversial. Many responded positively to Satin's new direction. A professor of management, for example, wrote that unlike Satin's former newsletter, Radical Middle spoke about "reality".[191] Scholarly books began citing articles from the newsletter.[192] In a book on globalization, Walter Truett Anderson said Radical Middle "carries the encouraging news of an emerging group with a different voice, one that is 'nuanced, hopeful, adult'. ... It is essentially a willingness to listen to both sides of the argument."[186] But three objections were often heard. Some critics accused Satin of misguided policy proposals, as when peace studies scholar Michael N. Nagler wrote that the article "praising humanitarian military intervention as the 'peace movement' of our time, is nothing short of an insult ... to the real peace movement" [emphasis in original].[193] Other critics accused Satin of abandoning his old constituency, as when author and former New Options advisor David Korten chided him for consciously choosing pragmatism over idealism.[194] There were also accusations of elitism, as when the executive editor of Yes! magazine said Satin favored globalization because it appealed to his interests and those of his "law school buddies".[195]

New Options Newsletter was based on the theories set forth in New Age Politics.[134] But Satin's approach to his radical middle project was eclectic and experimental.[196] His contribution to radical centrist political theory, the book Radical Middle, was not published until 2004, the newsletter's sixth year. Until then, the only glimpse Satin gave of his larger vision appeared in an article he wrote for an academic journal.[197]

Radical Middle, the book

[edit]Satin's book Radical Middle: The Politics We Need Now, published by Westview Press and Basic Books in 2004, attempts to present radical centrism as a political ideology.[198] It is considered one of the two or three "most persuasive"[199] or most representative[200][201] books on the subject, and it received the "Best Book Award" for 2003 and 2004 from the Section on Ecological and Transformational Politics of the American Political Science Association.[202] It also generated – like all of Satin's works – criticism and controversy.

Satin presents Radical Middle as a revised and evolved version of his New Age Politics book, rather than as a rejection of it.[7] Some observers had always seen him as a radical centrist. As early as 1980, author Marilyn Ferguson identified him as part of what she called the "Radical Center".[203] In 1987, culture critic Annie Gottlieb said Satin was trying to prompt the New Age and New Left to evolve into a "New Center".[146] But the revisions Satin introduces are substantial. Instead of defining politics as a means for creating the ideal society, as he did in New Age Politics,[105] he defines radical middle politics as "idealism without illusions"[nb 20] – more creative and future-oriented than politics-as-usual, but willing to face "the hard facts on the ground".[198] Rather than arguing that change will be brought about by a third force, he says most Americans are already radical middle – "we're very practical folks, and we're very idealistic and visionary as well."[187]

Although Satin argues in New Age Politics that Americans need to change their consciousness and decentralize their institutions,[134] in Radical Middle he says they can build a good society if they adopt and live by Four Key Values: maximize choices for all Americans, give every American a fair start, maximize every American's human potential, and help the peoples of the developing world. Instead of finding those values in the writings of contemporary theorists, Satin says they are just new versions of the values that inspired 18th-century American revolutionaries: liberty, equality, pursuit-of-happiness, and fraternity, respectively. He calls Benjamin Franklin the radical middle's favorite Founding Father, and says Franklin "wanted us to invent a uniquely American politics that served ordinary people by creatively borrowing from all points of view."[205][nb 21]

In New Age Politics, Satin chooses not to focus on the details of public policy.[207] In Radical Middle, however, Satin develops a raft of policy proposals rooted in the Four Key Values. (Among them: universal access to private, preventive health insurance, class-based rather than race-based affirmative action, mandatory national service, and opening U.S. markets to more products from poor nations.) In New Age Politics, Satin calls on "life-oriented" people to become radical activists for a New Age society. In Radical Middle, Satin calls on people of every political stripe to work from within for social change congruent with the Four Key Values.[205]

"I think most of us secretly know – and those of us at the radical middle are inclined to say – that without such concepts as duty and honor and service, no civilization can endure. ... I suspect most Americans would respond positively to a [draft] if it gives us some choice in how to exercise that duty and service. ... Exactly the kind of choice my generation did not have during the Vietnam War."

– Mark Satin in 2004, on mandatory national service and the individual conscience.[208]

Satin's mandatory national service proposal drew significant media coverage,[187][209] in part because of his status as a draft refuser.[210] Satin argues that a draft could work in the United States if it applied to all young people, without exception, and if it gave everyone a choice in how they would serve.[187] He proposes three service options: military (with generous benefits), homeland security (at prevailing wages), and community care (at subsistence wages).[211] On Voice of America radio, Satin presented his proposal as one drawing equally from the best of the left and the right.[209] On National Public Radio, he emphasized its fairness.[187]

Radical Middle provokes three kinds of responses: skeptical, pragmatic, and visionary. Skeptical respondents tend to find Satin's beyond-left-and-right policy proposals to be unrealistic and arrogant. For example, political writer Charles R. Morris says "Satin's nostrums" echo the "glibness and overweening self-confidence ... in Roosevelt's brain trust, or in John F. Kennedy's."[212] Similarly, the policy director of the Democratic Leadership Council says Satin's book "ultimately places him in the sturdy tradition of 'idealistic' American reformers who think smart and principled people unencumbered by political constraints can change everything."[213]

Pragmatic observers tend to applaud Satin's willingness to borrow good ideas from the left and the right.[198] But these respondents are typically more drawn to Satin as a policy advocate – or as a counterweight to partisan militants like Ann Coulter[214] – than they are to him as a political theorist. For example, Robert Olson of the World Future Society warns Satin against presenting the radical middle as a new ideology.[198]

Visionary respondents typically appreciate Satin's work as a policy advocate. But they also see him as attempting something rarer and, according to spiritual writer Carter Phipps, richer – raising politics to a higher level by synthesizing truths from all the political ideologies.[9] Author Corinne McLaughlin identifies Satin as one of those creating an ideology about ideologies.[215] She quotes him:

Coming up with a solution is not a matter of adopting correct political beliefs. It is, rather, a matter of learning to listen – really, listen – to everyone in the circle of humanity, and to take their insights into account. For everyone has a true and unique perspective on the whole. [Many] years ago the burning question was, How radical are you? Hopefully someday soon the question will be, How much can you synthesize? How much do you dare to take in?[216]

Later life

[edit]Life changed for Satin after writing and publicizing his Radical Middle book. In 2006, at the age of 60, he moved from Washington, D.C., to the San Francisco Bay Area to reconcile with his father, from whom he had been estranged for 40 years.[15] "With the perspective of time and experience," Satin told one reporter, "I can see [my father] was not altogether out to lunch."[15] Later that year Satin discovered his only life partner. He describes it as "no accident".[140]

In 2009 Satin revealed he was losing his eyesight as a result of macular edema and diabetic retinopathy.[140] He stopped producing Radical Middle Newsletter but expressed a desire to write a final political book.[140] From 2009 to 2011 he presented occasional guest lectures on "life and political ideologies" in peace studies classes at the University of California, Berkeley.[217] In 2015 he helped produce a "40th Anniversary Edition" of his book New Age Politics,[218] and in 2017 he helped produce a 50th anniversary edition of his Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada.[56]

Up From Socialism

[edit]In his mid-70s, Satin wrote the book Up From Socialism (2023).[219] It was edited by Adam Bellow, a son of the novelist Saul Bellow.[220] Shortly after publication, Satin described what he saw as the book's political perspective on the Civil Rights Movement Archive website: "[In my new book], radical politics no longer means taking an extreme side of an issue and acting as if you're right and everyone else is wrong (or, especially today, 'evil'). Rather, it means listening empathically to the fears, needs, wants, and wisdom of people on all sides of an issue, and then working with all sides to develop genuine (not mushy-middle) solutions that address everyone's core interests. That is the kind of movement we need today, not a revival of the movements of the Sixties".[221]

Assessment

[edit]Mark Satin has been a controversial public figure since the age of 20. Assessments of his significance vary widely.

Some observers see him as an exemplary figure. David Armstrong, for example, in his study of independent American journalism, presents Satin as an embodiment of the "do-it-yourself spirit" that makes an independent press possible.[93] Futurists Jessica Lipnack and Jeffrey Stamps portray Satin as a pioneer "networker" who spent two years riding the bus across the U.S. in an attempt to connect like-minded thinkers and activists.[125] Marilyn Ferguson, author of The Aquarian Conspiracy, says that by engaging in a lifelong series of personal and political experiments with few resources, Satin is playing the role of the holy "Fool" for his time.[6]

Other observers stress the freshness of Satin's political vision. Social scientists Paul Ray and Sherry Anderson, for example, argue that Satin anticipated the perspectives of 21st century social movements better than nearly anyone.[92][nb 22] Humanistic psychologist John Amodeo says Satin is one of the few political theorists to grasp the connection between personal growth and constructive political change.[222] Ecofeminist Greta Gaard claims that Satin "played a significant role in facilitating the articulation of Green political thought".[223] Policy analyst Michael Edwards sees Satin as a pioneering trans-partisan thinker.[224] Peace researcher Hanna Newcombe finds a spiritual dimension in Satin's politics.[nb 23] Political scientist Christa Slaton's short list of "nonacademic" transformationalists consists of Alvin and Heidi Toffler, Fritjof Capra, Marilyn Ferguson, Hazel Henderson, Betty Friedan, E. F. Schumacher, John Naisbitt, and Mark Satin.[1]

Some see Satin as a classic example of the perpetual rebel and trace the cause back to his early years. For example, author Roger Neville Williams focuses on the harshness and "paternalistic rectitude" of Satin's parents.[20] Novelist Dan Wakefield, writing in The Atlantic, says Satin grew up in a small city in northern Minnesota like Bob Dylan but did not have a guitar to express himself with.[18] According to historian Frank Kusch, the seeds for rebellion were planted when Satin's parents moved him at age 16 from liberal Minnesota to still-segregated Texas.[230]

Although many observers praise or are intrigued by Satin, many find him dismaying. Memoirist George Fetherling, for example, remembers him as a publicity hound.[52] Literary critic Dennis Duffy calls him incapable of learning from his experiences.[83] Green Party activist Howie Hawkins sees him as "virulently anti-left".[231] The Washington Monthly portrayed him in his 50s as a former New Age "guru",[213] and Commonweal compares reading him to listening to glass shards grate against a blackboard.[212]

Other observers see Satin as an emotionally wounded figure. For example, historian Pierre Berton calls him a "footloose wanderer" and says he hitchhiked across Canada 16 times.[33] Culture critic Annie Gottlieb, who attributes Satin's wounds to his struggle against the Vietnam War, points out that even as a successful newsletter publisher in Washington, DC, he paid himself the salary of a monk.[232]

The major substantive criticisms of Satin's work have remained constant over time. His ideas are sometimes said to be superficial; they were characterized as childish in the 1960s,[13] naive in the 1970s,[233] poorly reasoned in the 1980s[120] and 1990s,[234] and overly simple in the 2000s.[235] His ideas have also occasionally been seen as not politically serious,[236] or as non-political in the sense of not being capable of challenging existing power structures.[237] His work is sometimes said to be largely borrowed from others, a charge that first surfaced with regard to his draft dodger manual,[10][52] and was repeated to varying degree by critics of his books on New Age politics[106] and radical centrism.[213]

Satin has long been faulted for mixing views from different parts of his political odyssey. In the 1970s, for example, Toronto Star editor Robert Nielsen argued that Satin's leftist pacifism warps his New Age vision.[105] Three decades later, public-policy analyst Gadi Dechter argued that Satin's New Age emotionalism and impracticality blunt his radical-centrist message.[238] At 58, Satin suggested his message could not be understood without appreciating all the strands of his personal and political journey:

From my New Left years I took a love of political struggle. From my New Age years I took a conviction that politics needs to be about more than endless struggle – that responsible human beings need to search for reconciliation and healing and mutually acceptable solutions. From my time in the legal profession I took an understanding (and it is no small understanding) that sincerity and passion are not enough – that to be truly effective in the world one needs to be credible and expert. ...

Many Americans are living complicated lives now – few of us have moved through life in a straight line. I think many of us would benefit from trying to gather and synthesize the difficult political lessons we've learned over the course of our lives.[144]

Publications

[edit]Books

[edit]- Up From Socialism: My 60-Year Search for a Healing New Radical Politics, Bombardier Books / Post Hill Press, distributed by Simon & Schuster, 2023. ISBN 978-1-63758-663-1. Strengths and weaknesses of the "post-socialist" wing of the social change movement.

- Radical Middle: The Politics We Need Now, Basic Books, 2004, orig. Westview Press, 2004. ISBN 978-0-8133-4190-3. Radical-centrist ideas presented as an integrated political ideology.

- New Options for America: The Second American Experiment Has Begun, foreword by Marilyn Ferguson, The Press at California State University, 1991. ISBN 978-0-8093-1794-3. Twenty-five cover stories from Satin's New Options Newsletter.

- New Age Politics: Healing Self and Society, Delta Books / Dell Publishing Co., 1979. ISBN 978-0-440-55700-5. New Age political ideas presented as an integrated political ideology.[nb 8]

- Confessions of a Young Exile, Gage Publishing Co. / Macmillan of Canada, 1976. ISBN 978-0-7715-9954-5. Memoir covering the years 1964–66.

- Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada, House of Anansi Press, 1968. [ISBN unspecified]. OCLC 467238. Preserve oneself and change the world. Satin wrote Part One ("Applying") and solicited and edited the materials in Part Two ("Canada"). OCLC retrieved December 13, 2013.[nb 24]

Newsletters

[edit]- Radical Middle Newsletter, 120 issues, 1999–2009. ISSN 1535-3583. Originally hard-copy only, now largely online. Newsletter retrieved April 17, 2011, ISSN retrieved September 28, 2011.

- New Options Newsletter, 75 issues, 1984–1992. ISSN 0890-1619. Originally hard-copy only, now partially online. Newsletter retrieved October 18, 2014, ISSN retrieved September 28, 2011.

Selected articles and interviews

[edit]- "Godfrey and Me", House of Anansi Press website, June 14, 2017. How Satin convinced Anansi to publish his Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada. Retrieved April 4, 2019.

- "The New Age 40 Years Later", The Huffington Post, April 25, 2016. Interview by Rick Heller of the Humanist Community at Harvard. Retrieved July 16, 2016.

- "The Three Committees", Civil Rights Movement Archive website, "Activists" section, "Our Stories" sub-section, 2015. Website sponsored by Duke University Libraries and others. Semi-autobiographical short story about being an estranged Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee volunteer in Mississippi in 1965. Retrieved May 26, 2024.

- "Mark Satin on the Politics of the Radical Middle", National Public Radio audiotape, July 9, 2004. Interview by Tony Cox for The Tavis Smiley Show. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- "Where's the Juice?", The Responsive Community, vol. 12, no. 4 (2002), pp. 70–75. Critical review of Ted Halstead and Michael Lind's book The Radical Center. Retrieved April 17, 2011

- "Law and Psychology: A Movement Whose Time Has Come", Annual Survey of American Law, vol. 51, no. 4 (1994), pp. 583–631. Early argument for what is now called "therapeutic jurisprudence".

- "20th Anniversary Rendezvous: Mark Satin", Whole Earth Review, issue no. 61, winter 1988, p. 107. Interview by Kevin Kelly.

- "Do-It-Yourself Government", Esquire, vol. 99, no. 4 (April 1983), pp. 126–28. Early attempt to present New Age political ideas as pragmatic and centrist.

See also

[edit]- Canada and the Vietnam War

- List of futurologists

- List of peace activists

- S. H. Rider High School

- Transformative social change

Notes

[edit]- ^ This slogan first appeared in Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung, and was later taken up by factions of the New Left.[8]

- ^ Satin mentions this incident in his Radical Middle book, but omits the name of the university.[7] An article from September 1967 also mentions the incident without naming the university, but adds that Satin's father taught there at the time.[23] An article from May 1967 tells where the father taught.[13]

- ^ From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, some U.S. state legislatures required students and professors at public universities to sign oaths of national loyalty.[24][25]

- ^ Applicants for immigrant status were expected to show that they had enough money to live on until they found work or otherwise established themselves.[44]

- ^ Satin later contributed to neopacifist theory by presenting a model for a largely nonviolent "evolutionary" movement in the United States.[46]

- ^ According to one author, every American who applied for Canadian immigrant status under Satin's direction eventually obtained it.[20]

- ^ In 2017, Canadian publishing historian Roy MacSkimming provided more detail, stating that 65,00 copies of the Manual had been sold by Canadian publishers, and another 30,000 had been reproduced in whole or in part by U.S. anti-war entities.[56] A Canadian literary magazine subsequently attributed to the Manual "the distinction of being one of this country's most pirated books".[57]

- ^ a b A "40th Anniversary Edition" of New Age Politics, condensed and updated by the author, with a new subtitle and a foreword by spiritual writer David Spangler, appeared in 2015.[239]

- ^ Satin's father had written a textbook about the achievements of Western civilization.[16]

- ^ Publication of Satin's book in Sweden was preceded by a large New Age conference near Stockholm featuring Satin, Hazel Henderson, and Carl Rogers.[108]

- ^ The German edition of New Age Politics includes contributions from writers born in Germany, Austria, and Britain.

- ^ Bruno Langdahl, from Denmark, has prepared a bibliography featuring European as well as American writing on New Age ideology. It includes two books by Satin, New Age Politics and Radical Middle.[111] Slavoj Žižek, from Slovenia, has criticized New Age ideology from a radical-left perspective without reference to Satin or any member of Satin's New Options Newsletter advisory board. Among New Age writers, Žižek pays particular attention to James Redfield, Colin Wilson, and advocates of Jungian psychology.[112]

- ^ Some authors identify similarities between the New Age and Green approaches. For example, education theorist Ron Miller says that both Satin's New Age politics and Europe's Green politics seek to "maintain a balance between the existential and the political, the personal and the social".[114] University of Urbino researcher Stefano Scoglio says that both Satin's book New Age Politics (1978) and Charlene Spretnak and Fritjof Capra's book Green Politics (1986) stress "the need to reunite politics and spirituality".[115]

- ^ Cloud devotes chapters in two books to comparing Satin's New Age Politics to the work of non-North American post-Marxists, particularly Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe.[123][124]

- ^ Although Carter is often said to have granted "amnesty", he avoided that term on the grounds that it might be taken to imply approval or support.[126] Instead, he offered an unconditional "pardon" to Vietnam-era draft resisters, and less-than-honorable discharges to Vietnam-era military deserters.[127]

- ^ According to one New Age magazine, Satin traveled over 55,000 miles during his combined book and organizing tour, mostly by Greyhound bus. He spoke at over 50 venues, including a cultural center in Harlem, the World Symposium on Humanity in Los Angeles, and the Institute of Politics at Harvard.[128]

- ^ $91,000 in 1983 was equal to over $230,000 in 2013.[138]

- ^ In 2018, British scholar Aidan Rankin said that the "technique of questioning" of the original Ten Key Values statement was useful because it could help the political right and left find "unexpected common ground" with others.[173] An "attitude of questioning", he added, "is a more practical response to increasing complexity in economics, the environment and technology than adopting absolutist positions".[173]

- ^ Satin maintained District of Columbia Bar membership into the 2020s.[183]

- ^ This phrase, unattributed by Satin, is credited to John F. Kennedy by Kennedy biographer Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.[204]

- ^ Satin claims that his interpretation of Franklin is supported by Walter Isaacson's biography Benjamin Franklin: An American Life (2003).[206]

- ^ The authors devote the opening of their "Converging Movements" section to telling Satin's story, then name six "other visionaries": George Leonard, Marilyn Ferguson, Alvin Toffler, Fritjof Capra, Hazel Henderson, and Theodore Roszak.[92]

- ^ Newcombe points to a Teilhardian element in Satin's work.[225] Spiritual writer Anna Lemkow sees an overlap with theosophy.[226] Anthropologist Armin Geertz identifies a prophetic dimension (but finds it inauthentic).[227] Christian scholar Norman Geisler describes Satin's environmentalism, disapprovingly, as pantheistic.[228] Rick Fields, an authority on Buddhism, says some of Satin's political ethics could form the basis of a society "in harmony with diverse spiritual beliefs".[229]

- ^ A 50th anniversary edition of the Manual, with an introduction by Canadian political economist James Laxer and a 10-page afterword by Satin, appeared in 2017.[240]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Christa Daryl Slaton, "An Overview of the Emerging Political Paradigm: A Web of Transformational Theories", in Stephen Woolpert, Christa Daryl Slaton, and Edward W. Schwerin, eds., Transformational Politics: Theory, Study, and Practice, State University of New York Press, 1998, p. 11. ISBN 978-0-7914-3945-6.

- ^ a b c Jeff Rosenberg, "Mark's Ism: New Options's Editor Builds a New Body Politic", Washington City Paper, March 17, 1989, pp. 6–8.

- ^ a b Dana L. Cloud, "'Socialism of the Mind': The New Age of Post-Marxism," in Herbert W. Simons and Michael Billig, eds., After Postmodernism: Reconstructing Ideology Critique, Sage Publications, 1994, p. 235. ISBN 978-0-8039-8878-1.

- ^ Timothy Miller, The Hippies and American Values, University of Tennessee Press, 1991, p. 139. ISBN 978-0-87049-693-6.

- ^ a b James Adams, "'The Big Guys Keep Being Surprised By Us'", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), October 20, 2007, p. R6. Retrieved December 7, 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marilyn Ferguson, "Foreword", in Mark Satin, New Options for America: The Second American Experiment Has Begun, The Press at California State University / Southern Illinois University Press, 1991, pp. xi–xiii. ISBN 978-0-8093-1794-3.

- ^ a b c d e f g Mark Satin, Radical Middle: The Politics We Need Now, Basic Books, 2004, orig. Westview Press, 2004, pp. 28–30. ISBN 978-0-8133-4190-3.

- ^ Paul Berman, A Tale of Two Utopias: The Political Journey of the Generation of 1968, W. W. Norton & Company, 1997, p. 175. ISBN 978-0-393-31675-9.

- ^ a b Carter Phipps, "Politics Gets Inclusive", What Is Enlightenment?, June–August 2005, p. 29.

- ^ a b c d John Hagan, Northern Passage: American Vietnam War Resisters in Canada, Harvard University Press, 2001, pp. 74–78. ISBN 978-0-674-00471-9.

- ^ a b c The Editors, "New Students, Seasoned Pros", The Law School: The Magazine of the New York University School of Law, spring 1993, p. 9.

- ^ Kirkpatrick Sale, SDS, Vintage Books / Random House, 1973, pp. 204–07. ISBN 978-0-394-71965-8.

- ^ a b c d e f Oliver Clausen, "Boys Without a Country", The New York Times Magazine, May 21, 1967, pp. 25 and 96–98.

- ^ a b c d John Burns, "Deaf to the Draft: Called in US, but Asleep in Toronto", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), October 11, 1967, pp. 1–2. A large head shot of Satin is on p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lynda Hurst, "A Picture and a Thousand Words", Toronto Star, August 24, 2008, "Ideas" section, p. 8. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Joseph Satin, The Humanities Handbook, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969. ISBN 978-0-03-071140-4.

- ^ Mark Satin, Confessions of a Young Exile, Gage Publishing Co. / Macmillan of Canada, 1976, pp. 6–8. ISBN 978-0-7715-9954-5.

- ^ a b Dan Wakefield, "Supernation at Peace and War", The Atlantic, March 1968, p. 42.

- ^ Satin, Confessions, Chap. 1.

- ^ a b c d e f Roger Neville Williams, The New Exiles: American War Resisters in Canada, Liveright Publishers, 1971, pp. 62–65. ISBN 978-0-87140-533-3.

- ^ Satin, Confessions, Chap. 2.

- ^ Satin, Confessions, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d e f Anastasia Erland, "Faces of Conscience I: Mark Satin, Draft Dodger", Saturday Night, September 1967, pp. 21–23. Cover story.

- ^ Doug Rossinow, The Politics of Authenticity: Liberalism, Christianity, and the New Left in America, Columbia University Press, 1998, pp 43–45. Discusses the establishment of loyalty oath requirements at public universities, particularly in Texas. ISBN 978-0-231-11056-3.

- ^ M. J. Heale, McCarthy's Americans: Red Scare Politics in State and Nation, 1935–1965, University of Georgia Press, 1998, pp 51–53. Discusses the gradual abolition of loyalty oath requirements. ISBN 978-0-8203-2026-7.

- ^ Satin, Confessions, pp. 187–88.

- ^ Satin, Confessions, pp. 1 and 203–07.

- ^ a b c Earl McRae, "US Draft Dodgers in Toronto: Safe – and Lonely", Toronto Star, August 5, 1967, p. 8.

- ^ Williams, New Exiles, pp. 45–48.

- ^ a b Michael S. Foley, Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance During the Vietnam War, University of North Carolina Press, 2003, p. 78. ISBN 978-0-8078-2767-3.

- ^ Charles DeBenedetti, An American Ordeal: The Antiwar Movement of the Vietnam Era, Syracuse University Press, 1990, pp. 129–30. ISBN 978-0-8156-0245-3.

- ^ Anne Morrison Welsh, Held in the Light: Norman Morrison's Sacrifice for Peace and His Family's Journey of Healing, Orbis Books, 2008, pp. 3–6. ISBN 978-1-57075-802-7.

- ^ a b c d Pierre Berton, 1967: The Last Good Year, Doubleday Canada, 1997, pp. 198–203. ISBN 978-0-385-25662-9.

- ^ Sale, SDS, pp. 364–65.

- ^ a b Jan Schreiber, "Canada's Haven for Draft Dodgers", The Progressive, January 1968, pp. 34–36.

- ^ a b c d David S. Churchill, "An Ambiguous Welcome: Vietnam Draft Resistance, the Canadian State, and Cold War Containment", Histoire Sociale / Social History, vol. 37, no. 73 (2004), pp. 6–9.

- ^ Renée G. Kasinsky, Refugees from Militarism: Draft-Age Americans in Canada, Transaction Books, 1976, p. 98. ISBN 978-0-87855-113-2.

- ^ a b c Mark Satin, "Afterword. Bringing Draft Dodgers to Canada in the 1960s: The Reality Behind the Romance", in Mark Satin, Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada, The A List / House of Anansi Press, 2017, pp. 127–29. ISBN 978-1-4870-0289-3.

- ^ a b John Maffre, "Draft Dodgers Conduct Own Anti-U.S. Underground War from Canadian Sanctuary", The Washington Post, January 22, 1967, p. E1.

- ^ Satin, "Afterword", p. 132, items #n and t.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Joseph Jones, "The House of Anansi's Singular Bestseller", Canadian Notes & Queries, issue no. 61, spring–summer 2002, pp. 19–21.

- ^ a b Mark Satin, ed., Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada, House of Anansi Press, 2nd ed., 1968, Chap. 1. [ISBN unspecified]. OCLC 467238. Retrieved December 13, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f Edward Cowan, "Expatriate Draft Evaders Prepare Manual on How to Immigrate to Canada", The New York Times, February 11, 1968, p. 7.

- ^ Satin, ed., Manual, 2nd ed., p. 17.

- ^ Helen Worthington, "She Gives Tea, Sympathy – and Jobs – to Draft Dodgers", Toronto Star, October 21, 1967, p. 65.

- ^ Mark Satin, New Age Politics: Healing Self and Society, Delta Books / Dell Publishing Co., 1979, Part VII. ISBN 978-0-440-55700-5.

- ^ For more on neopacifist activism in the 1960s, see:

- Clayborne Carson, In Struggle: SNCC and the Black Awakening of the 1960s, Harvard University Press, 1981, Chaps. 6–12. ISBN 978-0-674-44726-4.

- Marty Jezer, Abbie Hoffman: American Rebel, Rutgers University Press, 1992, Chaps. 3–5. ISBN 978-0-8135-1850-3.

- ^ Gary Dunford, "Toronto's Anti-Draft Office Jammed; Korea, New Viet Attacks Said Cause", Toronto Star, February 3, 1968, p. 25.

- ^ Glenn McCurdy, "The American Draft Resisters in Canada", Chicago Tribune, March 10, 1968, pp. F26, F70.

- ^ Jules Witcover, The Year the Dream Died: Revisiting 1968 in America, Warner Books, 1997, p. 6. ISBN 978-0-446-67471-3.

- ^ a b Myra MacPherson, Long Time Passing: Vietnam and the Haunted Generation, Doubleday and Company, 1984, p. 357. ISBN 978-0-385-15842-8.

- ^ a b c George Fetherling, Travels By Night: A Memoir of the Sixties, McArthur & Company Publishing, 2000, orig. 1994, p. 138. ISBN 978-1-55278-132-6.

- ^ Satin, "Afterword", pp. 134–35.

- ^ a b c d e Williams, New Exiles, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Patricia Hluchy, "1968 Was a Tumultuous Year of Protest in Cities Around the World", Toronto Star, June 1, 2008, p. 6. Retrieved September 14, 2011.

- ^ a b c Roy MacSkimming, "Review: Mark Satin's Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada Is Just as Timely as Ever", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), August 26, 2017, p. R12. Online dated one day earlier. Retrieved August 28, 2017.

- ^ Unidentified author, "What's Old", CNQ: Canadian Notes & Queries, issue no. 100, fall 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Paul Lauter and Florence Howe, "The Draft and Its Opposition", The New York Review of Books, June 20, 1968, p. 30. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Gary Dunford, "'Forgettable' Toronto – Where There's NO Draft", Toronto Star, February 14, 1968, pp. 1, 4.

- ^ Satin, ed., Manual, 2nd ed., Chaps. 26–40.

- ^ Satin, ed., Manual, 2nd ed., p. 6.

- ^ John Burns, "Canadians Don't Live in Igloos, Draft Dodgers' Manual Advises", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), February 15, 1968, pp. 1, 2.

- ^ Eva-Marie Kroller, "Introduction", in Eva-Marie Kroller, ed., The Cambridge Companion to Canadian Literature, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 18. ISBN 978-0-521-81441-6.

- ^ a b Lynn Coady, "Introduction", in Lynn Coady, ed., The Anansi Reader: Forty Years of Very Good Books, House of Anansi Press, 2007, p. 5. ISBN 978-0-88784-775-2.

- ^ Editorial, "Don't Incite U.S. Draft Dodgers", Toronto Star, January 30, 1968, p. 6.

- ^ Barry Craig, "5,000 Manuals Published Here for U.S. Draft Dodgers", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), February 12, 1968, p. 5.

- ^ Harry F. Rosenthal, "Canada Increasingly Draft Dodgers' Haven", Los Angeles Times, June 2, 1968, p. H19.

- ^ Robert Fulford, "1968 – The Bogus Revolution", National Post (Toronto), March 29, 2008, p. 27. Retrieved April 17, 2011.

- ^ Satin, "Afterword", p. 135.

- ^ Elizabeth Renzetti, "Welcome to Canada, Americans! We Put the You in Neighbour", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), July 1, 2016 (Internet edition), July 2, 2016, p. 2 (print edition). Retrieved July 26, 2016.

- ^ John Boyko, The Devil’s Trick: How Canada Fought the Vietnam War, Knopf Canada, 2021, pp. 113–114. ISBN 9780735278004.

- ^ Jessica Squires, Building Sanctuary: The Movement to Support Vietnam War Resisters in Canada, 1965-73, University of British Columbia Press, 2013, pp. 34–37. ISBN 978-0-7748-2524-5.

- ^ Amiel Gladstone, Hippies and Bolsheviks and Other Plays, Coach House Books, 2007, pp. 90–92 (title play). ISBN 978-1-55245-183-0.

- ^ David Kieran, "Hell No, He Must Go!", Slate online magazine, February 7, 2017, para. #6. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Luke Stewart, "Review Essay: Manual for Draft-Age Immigrants to Canada", Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies, no. 85, December 2018, pp. 219–223. Published in French and English by Association Française d'Études Canadiennes, Institut des Amériques, France. Retrieved May 20, 2019.

- ^ Matthew McKenzie Bryant Roth, Crossing Borders: The Toronto Anti-Draft Programme and the Canadian Anti-Vietnam War Movement, M.A. Thesis in History, University of Waterloo, 2008, pp. 18–33. Retrieved August 28, 2011.

- ^ Robert Fulford, "How Vietnam War Draft Dodgers Became a Lively and Memorable Part of Canadian History", National Post (Canada), national edition, September 6, 2017, p. B5. Retrieved September 13, 2017.

- ^ William Zinsser, "Introduction", in William Zinsser, ed., Inventing the Truth: The Art and Craft of Memoir, Mariner Books / Houghton Mifflin, 1998, p. 3. ISBN 978-0-395-90150-2.

- ^ Ruth Panofsky, The Literary Legacy of the Macmillan Company of Canada, University of Toronto Press, 2012, p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8020-9877-1.

- ^ John Lazarus, "Q's Reviews: Confessions of a Young Exile", printed transcript, CHQM-FM (Vancouver), December 16, 1976, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Jackie Hooper, "Satin Confesses He Talked Himself Into Exile", The Province (Vancouver), October 4, 1976, p. 20.

- ^ Roy MacSkimming, "A Young Exile's Novel: Anxious, Guilt-Ridden", Toronto Star, June 11, 1976, p. E8.

- ^ a b Dennis Duffy, "Perhaps Somewhere a Turgenev Is Waiting", The Globe and Mail (Toronto), June 12, 1976, p. 34.

- ^ a b Rachel Adams, "'Going to Canada': The Politics and Poetics of Northern Exodus", Yale Journal of Criticism, vol. 18, no. 2 (fall 2005), pp. 417–24. Reproduced at the Project MUSE digital database. Retrieved September 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Robert McGill, War Is Here: The Vietnam War and Canadian Literature, McGill-Queen's University Press, 2017, pp. 172–74, 177–81. ISBN 978-0-7735-5159-6.

- ^ Adams, "Going", p. 417 ("... literary representations of the draft dodger").

- ^ McGill, War, p. 172 ("Draft-Dodger Novels").

- ^ Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage, Bantam Books, 1987, Chap. 18. ISBN 978-0-553-05233-6.

- ^ Marilyn Ferguson, The Aquarian Conspiracy: Personal and Social Transformation in the 1980s, Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc., 1980, Chaps. 7–11. ISBN 978-0-87477-191-6.

- ^ Gitlin, The Sixties, Chap. 19.

- ^ Satin, New Age Politics, Dell edition, p. 1.

- ^ a b c d e Paul H. Ray and Sherry Ruth Anderson, The Cultural Creatives: How 50 Million People Are Changing the World, Harmony Books / Random House, 2000, pp. 206–07. ISBN 978-0-609-60467-0.

- ^ a b David Armstrong, A Trumpet to Arms: Alternative Media in America, Jeremy P. Tarcher Inc. / South End Press, 1981, pp. 315–16. ISBN 978-0-89608-193-2.

- ^ Mark Satin, New Age Politics: Healing Self and Society, Whitecap Books, 1978. ISBN 978-0-920422-01-4.

- ^ David Spangler, "Foreword", in Mark Satin, New Age Politics: Our Only Real Alternative, Lorian Press, 2015, p. 15. ISBN 978-0-936878-80-5.

- ^ Harvey Wasserman, "The Politics of Transcendence", The Nation, August 11, 1985, pp. 146–47.

- ^ Carl Boggs, The End of Politics: Corporate Power and the Decline of the Public Sphere, Guilford Press, 2000, p. 170. ISBN 978-1-57230-504-5.

- ^ Andrew Ross, "New Age Technoculture", in Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula A. Treichler, eds., Cultural Studies, Routledge, 1991, p. 548. ISBN 978-0-415-90345-5.

- ^ a b Andrew Jamison, The Making of Green Knowledge: Environmental Politics and Cultural Transformation, Cambridge University Press, 2001, p. 5. ISBN 978-0-521-79252-3.

- ^ Satin, New Age Politics, Dell edition, p. 305.

- ^ a b This paragraph combines material from the following sources:

- Cloud, "Socialism of the Mind", pp. 231–40.

- Michael S. Cummings, "Mind Over Matter in the Prison", Alternative Futures, vol. 4, no. 1 (1981), pp. 158–66.

- Richard G. Kyle, "The Political Ideas of the New Age Movement", Journal of Church and State, vol. 37, no. 4 (1995), pp. 831–48.

- ^ Satin, New Age Politics, Dell edition, p. 255.

- ^ Some positive "movement" views of New Age Politics are expressed in:

- The Editors, "Inside", New Age Journal, April 1977, p. 6.

- Bonnie Kreps, "A Radical Feminist Looks at New Age Politics", Makara, vol. 2, no. 3 (1977), pp. 16–18.

- Unidentified author, "Mark Satin", Communities: Journal of Cooperative Living, issue no. 28, September–October 1977, p. 62.

- Donald Keys, "New Age Politics", One Family: Newsletter of Planetary Citizens, November 1977, p. 4.

- Gerry Dixon, "New Age Politics", Odyssey Magazine, February 1978, p. 40.

- Guy Dauncey, "A New Dance", Peace News, issue no. 2117, April 4, 1980, p. 14.

- Robert Thompson, "The Six-Sided Prison", Yoga Journal, November–December 1980, pp. 56–57.

- Greg MacLeod, New Age Business: Community Corporations That Work, Canadian Council on Social Development, 1986, p. 7. ISBN 978-0-88810-354-3.

- Harry Hay, Radically Gay: Gay Liberation in the Words of Its Founder, Beacon Press, 1996, p. 239. ISBN 978-0-8070-7080-2.

- ^ Sy Safransky, "Mark Satin, New Age Politics", The Sun, April 1981, p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Robert Nielsen, "A Slightly Flawed Blueprint for a Whole New Society", Toronto Star, January 26, 1977, p. B4. Editorial page.

- ^ a b John McClaughry, "What's This New Age Stuff?", Reason, vol. 12, issue no. 4 (August 1980), pp. 46–47. Retrieved March 25, 2014.

- ^ Mark Satin, Politik for en Ny Tid, Wahlström & Widstrand, 1981. Swedish language publication. [ISBN unspecified]

- ^ Erik Sidenbladh, "Kreativ Rörelse för 'Den Nya Tidsaldern'", Svenska Dagbladet (Stockholm), October 5, 1980, "Idag" section, p. 1. Swedish language publication.

- ^ Mark Satin, Heile dich selbst und unsere Erde, foreword by Fritjof Capra, Arbor Verlag, 1993. German language publication. ISBN 978-3-924195-01-4.

- ^ Stuart Rose, Transforming the World: Bringing the New Age Into Focus, Peter Lang AG, 2005, p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8204-7241-6.

- ^ Bruno Langdahl, New Age-Bevægelsens Politiske Tænkning – En Ideologianalyse Archived April 26, 2012, at the Wayback Machine, M.A. Thesis in Political Science, Aarhus University, 2008, pp. 103–08. Danish language publication.

- ^ Slavoj Žižek, The Ticklish Subject: The Absent Centre of Political Ontology, Verso Books, 2000, pp. 1–2, 70, 362–63, and 384–85. ISBN 978-1-85984-291-1.

- ^ Kenn Kassman, Envisioning Ecotopia: The U.S. Green Movement and the Politics of Radical Social Change, Praeger Publishers, 1997, pp. 121–22. ISBN 978-0-275-95784-1.

- ^ Ron Miller, Free Schools, Free People: Education and Democracy After the 1960s, State University of New York Press, 2002, p. 94. ISBN 978-0-7914-5420-6.

- ^ Stefano Scoglio, Transforming Privacy: A Transpersonal Philosophy of Rights, Praeger Publishers / Greenwood Publishing Group, 1998, pp. 38 and 50n.30. ISBN 978-0-275-95607-3.

- ^ Constance E. Cumbey, The Hidden Dangers of the Rainbow: The New Age Movement and Our Coming Age of Barbarism, Huntington House, Inc., 1983, p. 264. ISBN 978-0-910311-03-8.

- ^ Tim LaHaye and Ed Hindson, Seduction of the Heart: How to Guard and Keep Your Heart from Evil, W Publishing Group / Thomas Nelson, Inc., 2001, p. 178. ISBN 978-0-8499-1726-4.

- ^ Ron Rhodes, New Age Movement, Zondervan Publishing House, 1995, p. 20. ISBN 978-0-310-70431-7.

- ^ Douglas R. Groothuis, Unmasking the New Age, InterVarsity Press, 1986, p. 126. ISBN 978-0-87784-568-3.

- ^ a b Cummings, "Mind Over Matter", pp. 161–64.

- ^ David J. Hess, Science in the New Age, University of Wisconsin Press, 1993, p. 174. ISBN 978-0-299-13820-2.

- ^ Dana L. Cloud, Control and Consolation in American Culture and Politics: Rhetorics of Therapy, Sage Publications, 1998, p. 133. ISBN 978-0-7619-0506-6.

- ^ Cloud, Control and Consolation, pp. 131–56.

- ^ Cloud, "Socialism of the Mind," pp. 222–51.

- ^ a b c d e f Jessica Lipnack and Jeffrey Stamps, Networking: The First Report and Directory, Doubleday, 1982, pp. 107–08. ISBN 978-0-385-18121-1.

- ^ Hagan, Northern Passage, p. 167.

- ^ Hagan, Northern Passage, p. 176.

- ^ Alison Wells and Stanley Commons, "Moving Politics With Spirit (And Greyhound)", New Realities, June–July 1979, p. 23.