The Bourne Supremacy (film)

| The Bourne Supremacy | |

|---|---|

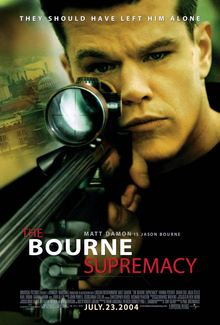

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Paul Greengrass |

| Screenplay by | Tony Gilroy |

| Based on | The Bourne Supremacy by Robert Ludlum |

| Produced by |

|

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Oliver Wood |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | John Powell |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release date |

|

Running time | 108 minutes |

| Countries | United States Germany[1] |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $75 million |

| Box office | $290.6 million |

The Bourne Supremacy is a 2004 action-thriller film featuring Robert Ludlum's Jason Bourne character. Although it takes the name of the second Bourne novel (1986), its plot is entirely different. The film was directed by Paul Greengrass from a screenplay by Tony Gilroy. It is the second installment in the Bourne franchise, a direct sequel to The Bourne Identity (2002).

The Bourne Supremacy continues the story of Jason Bourne, a former CIA assassin suffering from psychogenic amnesia.[2] Bourne is portrayed by Matt Damon. The film focuses on his attempt to learn more of his past as he is once more enveloped in a conspiracy involving the CIA and Operation Treadstone. Actors Brian Cox and Julia Stiles reprise their roles as Ward Abbott and Nicky Parsons, respectively. Joan Allen joins the cast as Deputy Director and Task Force Chief Pamela Landy.

Universal Pictures released the film to theaters in the United States on July 23, 2004, to positive reviews and commercial success, grossing $290 million on a $75 million budget. The film was followed by The Bourne Ultimatum (2007), The Bourne Legacy (2012), and Jason Bourne (2016).

Plot

[edit]Jason Bourne and Marie Kreutz are living in Goa, India. He is still suffering from amnesia, so records flashbacks about his life as a CIA assassin in a notebook.

In Berlin, a CIA agent working for Deputy Director Pamela Landy is paying $3 million to an unnamed Russian source for the Neski files, documents on the theft of $20 million seven years prior. The deal is interrupted by Kirill, a Russian Federal Security Service agent who works for oligarch Yuri Gretkov. He kills the agent and source, steals the files and money, and plants fingerprints framing Bourne for the attack.

After finding Bourne's fingerprint, Landy asks Section Chief Ward Abbott about Operation Treadstone, the defunct CIA program to which Bourne belonged. She tells Abbott that the CIA agent who stole the $20 million was named in the Neski files. Some years ago, Russian politician Vladimir Neski was about to identify the thief when he was killed by his wife in a suspected murder-suicide in Berlin. Landy believes that Bourne and Treadstone's late supervisor, Alexander Conklin, were involved and that Bourne killed the Neskis.

Gretkov directs Kirill to Goa to kill Bourne. He flees with Marie; Kirill follows and kills her, unaware that they switched seats in the midst of the chase. Bourne leaves Goa and travels to Naples, where he allows himself to be identified by security. He subdues a Diplomatic Security agent and a Carabinieri guard and copies the SIM card from his cell phone. From the subsequent phone call, he learns about Landy and the frame job.

Bourne goes to Munich to visit Jarda, the only other remaining Treadstone operative. Jarda informs him Treadstone was shut down after Conklin's death, then attacks him; Bourne strangles him to death, before destroying his home in a gas explosion as agents move in.

Bourne follows Landy and Abbott to Berlin as they meet former Treadstone support technician Nicky Parsons to question her about Bourne. Bourne believes the CIA is hunting him again and calls Landy from a nearby roof. He demands a meet-up with Nicky and indicates to Landy that he can see her in the office.

Bourne kidnaps Nicky in Alexanderplatz and learns from her that Abbott had been Conklin's boss. He releases her after she reveals she knows nothing about the mission. Bourne then visits the hotel where the killing took place and recalls more of his mission: he killed Neski on Conklin's orders, and when Neski's wife showed up, he shot her and made it look like a murder-suicide.

Danny Zorn, Conklin's former assistant, finds inconsistencies in the report of Bourne's involvement with the death of the agent and explains his theory to Abbott. Abbott then kills Zorn to prevent him from informing Landy.

Bourne breaks into Abbott's hotel room and records a conversation between him and Gretkov that incriminates them in the theft of the $20 million. When confronted, Abbott admits to Bourne that he stole the money, ordered Kirill to retrieve the files, and had Bourne framed before arranging for him to be silenced in Goa.

Abbott expects Bourne to kill him, but Bourne refuses, saying Marie would not want him to, and puts a gun on the table and leaves. Landy confronts Abbott about her suspicions and he kills himself; later, she finds an envelope containing the tape of Abbott's conversations with Gretkov and Bourne in her hotel room.

Bourne travels to Moscow to find Neski's daughter, Irena. Kirill, tasked once again by Gretkov with killing Bourne, finds and wounds him. Bourne flees in a stolen taxi and Kirill chases him. Bourne forces Kirill's vehicle into a concrete divider, and leaves behind a seriously wounded Kirill, as Gretkov is arrested with Landy watching in the background. Bourne locates Irena and confesses to murdering her parents, apologizing to her as he leaves.

Later in New York City, Bourne calls Landy. She thanks him for the tape, reveals his original name, David Webb, and his date and place of birth, and asks him to meet her. Bourne, who is watching her from a building tells her she looks tired and to get some rest, as he disappears into the city.

Cast

[edit]- Matt Damon as Jason Bourne: Amnesiac former assassin in the CIA's Operation Treadstone

- Franka Potente as Marie: Bourne's girlfriend

- Brian Cox as Ward Abbott: A corrupt CIA Section Chief, formerly directed Treadstone

- Julia Stiles as Nicky: CIA agent, brought from her post-Treadstone assignment to assist in the search for Bourne

- Karl Urban as Kirill: A corrupt Russian Federal Security Service assassin

- Gabriel Mann as Danny Zorn: CIA Treadstone analyst now assigned to Abbott's staff

- Joan Allen as Pamela Landy: CIA Deputy Director

- Marton Csokas as Jarda: Former Treadstone assassin

- Karel Roden as Yuri Gretkov: Kirill's employer

- Tomas Arana as Martin Marshall: CIA Director

- Tom Gallop as Tom Cronin: Landy's second-in-command agent

- Tim Griffin as Nevins

- Michelle Monaghan as Kim

- Ethan Sandler as Kurt

- John Bedford Lloyd as Teddy

In addition, Oksana Akinshina appears as Irena Neski.

Production

[edit]The producers replaced Doug Liman, who directed The Bourne Identity. This was mainly due to the difficulties Liman had with the studio when making the first film, and their unwillingness to work with him again. British director Paul Greengrass was selected to direct the film after the producers saw Bloody Sunday (2002), Greengrass' depiction of the Bloody Sunday shootings in Northern Ireland, at Gilroy's suggestion. Producer Patrick Crowley liked Greengrass' "sense of the camera as [a] participatory viewer", a visual style Crowley thought would work well for The Bourne Supremacy.[3] The film was shot in reverse order of its settings: some portions of the car chase and the film's ending were shot in Moscow, then most of the rest of the film was shot in and around Berlin, and the opening scenes in Goa, India were filmed last.[4][5]

"Two weeks before [the film's] release, [Greengrass] got together with its star, Matt Damon, came up with a new ending and phoned the producers saying the new idea was way better. And it would cost $200,000 and involve pulling Damon from the set of Ocean's Twelve for a re-shoot. Reluctantly the producers agreed—the movie tested 10 points higher with the new ending".[6]

Reception

[edit]Box office

[edit]The Bourne Supremacy grossed $116.2 million domestically (United States and Canada) and $114.4 million in other territories, for a worldwide total of $290.6 million, against a budget of $75 million.[7] Released Jul 23, 2004, it opened at No. 1 and spent eight of its first nine weeks in the Top 10 at the domestic box office.[8]

Critical response

[edit]On the review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, 82% of 197 critics' reviews are positive, with an average rating of 7.2/10. The website's consensus reads: "A well-made sequel that delivers the thrills."[9] As per the review aggregator Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 73 out of 100 based on 39 critic reviews, considered as "generally favorable".[10]

Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times gave the film 3 out of 4 stars, writing that it "treats the material with gravity and uses good actors in well-written supporting roles [that] elevates the movie above its genre, but not quite out of it."[11]

Accolades

[edit]At the 2005 Taurus World Stunt Awards, veteran Russian stunt coordinator Viktor Ivanov and Scottish stunt driver Gillie McKenzie won the "Best Vehicle" award for their driving in the Moscow car chase scene. Dan Bradley, the film's second unit director won the overall award for stunt coordinator.[12] The film ranks 454th on Empire's 2008 list of the 500 greatest movies of all time.[13]

| Year | Organization | Award | Category | Recipient | Result |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards | ASCAP Award | Top Box Office Films | John Powell | Won |

| 2005 | Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films, USA | Saturn Award | Best Actor | Matt Damon | Nominated |

| 2005 | Broadcast Film Critics Association | Critics Choice Award | Best Popular Movie | Nominated | |

| 2005 | Cinema Audio Society Awards | C.A.S. Award | Outstanding Achievement in Sound Mixing for Motion Pictures | Nominated | |

| 2005 | Edgar Allan Poe Awards | Edgar | Best Motion Picture Screenplay | Nominated | |

| 2005 | Empire Awards, UK | Empire Award | Best Actor | Matt Damon and Best Film | Won |

| 2005 | Empire Awards, UK | Empire Award | Best British Director of the Year | Paul Greengrass | Nominated |

| 2005 | London Critics Circle Film Awards | ALFS Award | Best British Director | Paul Greengrass | Nominated |

| 2005 | London Critics Circle Film Awards | ALFS Award | Scene of the Year | The Moscow Car Chase Sequence | Nominated |

| 2005 | MTV Movie Award | MTV Movie Award | Best Action Sequence | The Moscow Car Chase | Nominated |

| 2005 | MTV Movie Award | MTV Movie Award | Best Male Performance | Matt Damon | Nominated |

| 2005 | Motion Picture Sound Editors, USA | Golden Reel Award | Best Sound Editing in Domestic Features – Dialogue & ADR and Best Sound Editing in Domestic Features - Sound Effects and Foley | Nominated | |

| 2005 | People's Choice Awards, USA | People's Choice Award | Favorite Movie Drama | Nominated | |

| 2005 | Teen Choice Award | Teen Choice Award | Choice Movie Actor: Action | Matt Damon | Nominated |

| 2005 | Teen Choice Award | Teen Choice Award | Choice Movie: Action | Nominated | |

| 2005 | USC Scripter Award | USC Scripter Award | Tony Gilroy (Screenwriter) and Robert Ludlum (Author) | Nominated | |

| 2005 | World Soundtrack Award | World Soundtrack Award | Best Original Soundtrack of the Year — John Powell and Soundtrack Composer of the Year — John Powell | Nominated | |

| 2005 | World Stunt Awards | Taurus Award | Best Stunt Coordinator or 2nd Unit Director | Dan Bradley | Won[12] |

| 2005 | World Stunt Awards | Taurus Award | Best Work with a Vehicle | Viktor Ivanov, Gillie McKenzie | Won[12] |

| 2005 | World Stunt Awards | Taurus Award | Best Fight | Darrin Prescott and Chris O'Hara | Nominated[12] |

Soundtrack

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy". British Film Institute. London. Archived from the original on January 29, 2009. Retrieved September 30, 2012.

- ^ Bennett, Bruce (May 28, 2008). "Jason Bourne Takes His Case to MoMA". NYSun.com. Archived from the original on April 21, 2010. Retrieved September 10, 2009.

- ^ "Picking Up the Thread". Production notes Archived September 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Bourne Supremacy (2004). Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ "Setting Bourne's World". Production notes Archived September 14, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. The Bourne Supremacy (2004). Retrieved 2010-07-16.

- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy Production Notes | 2004 Movie Releases". madeinatlantis.com. Archived from the original on August 17, 2012. Retrieved December 30, 2022.

- ^ Armstrong, Stephen (June 8, 2008). "A whirlwind in action". The Guardian. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved January 30, 2021.

- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy | Domestic Weekly". Box Office Mojo. IMDb. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ "The Bourne Supremacy". Metacritic. Fandom, Inc. Retrieved June 10, 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (July 23, 2004). "Damon makes 'Bourne' a supreme thriller". Chicago Sun-Times. Archived from the original on January 26, 2021. Retrieved February 4, 2021 – via RogerEbert.com.

- ^ a b c d "2005 Winners & Nominees". Taurus World Stunt Awards. Archived from the original on November 9, 2021. Retrieved January 31, 2021.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Empire Features. Archived from the original on April 5, 2012.

External links

[edit]- 2004 films

- 2004 action thriller films

- 2000s spy thriller films

- American action thriller films

- American sequel films

- American spy thriller films

- Babelsberg Studio films

- Bourne (film series)

- Films about the Federal Security Service

- American films about revenge

- 2000s English-language films

- English-language German films

- Films directed by Paul Greengrass

- Films produced by Frank Marshall

- Films scored by John Powell

- Films with screenplays by Tony Gilroy

- Films set in 2004

- Films set in 2005

- Films set in Berlin

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in India

- Films set in Italy

- Films set in Moscow

- Films set in Munich

- Films set in Naples

- Films set in New York City

- 2000s crime thriller films

- American crime thriller films

- 2004 crime thriller films

- Films set in Russia

- Films set in the Netherlands

- Films shot in Goa

- Films shot in Italy

- Films shot in Moscow

- Films shot in Russia

- Films about United States Army Special Forces

- German action thriller films

- German sequel films

- The Kennedy/Marshall Company films

- Universal Pictures films

- Films shot in India

- 2000s American films

- 2000s German films

- English-language crime thriller films

- English-language action thriller films

- English-language spy thriller films